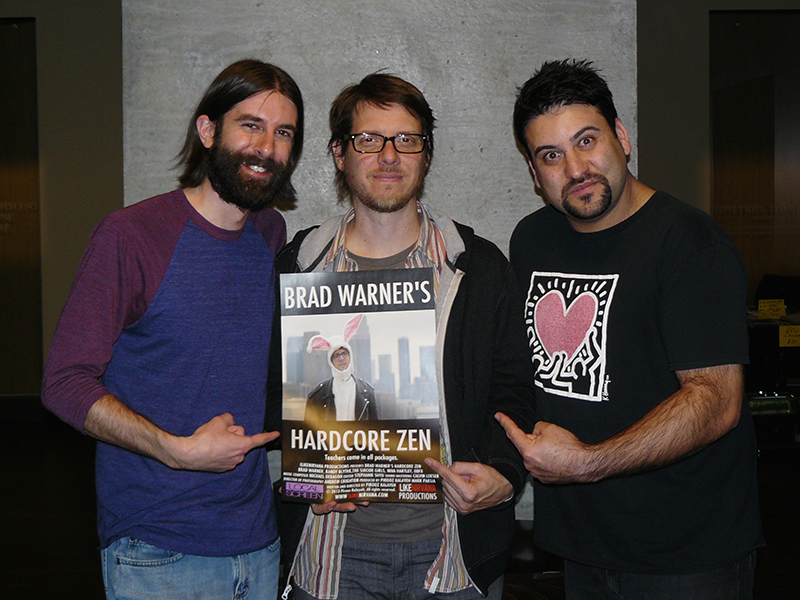

Zen Buddhist author Brad Warner and filmmaker Pirooz Kalayeh met with Nomos Journal’s Seth M. Walker last month to discuss Brad Warner’s Hardcore Zen at the Sie FilmCenter in Denver, Colorado. Brad and Pirooz have been traveling to different cities around the country for screenings and Q&A sessions since the film’s premiere at the Buddhist Film Festival in Amsterdam on October 5, 2013.

So how did this project come about?

Brad Warner: I wrote a book called Hardcore Zen: Punk Rock, Monster Movies and the Truth About Reality, which came out in 2003, and almost within like a month of it coming out there was a guy who contacted me about movie rights for it. I was living in Japan at the time and was kind of excited. So, I went out to Los Angeles, met the guy, talked to him, and he was really enthusiastic about making the movie. But this went on for a long time, and nothing happened. I had three other variations on that story, too. They would contact me and want to talk about the movie, and then they didn’t do anything. Each one was less exciting, and I became less interested with each one. By the time Pirooz contacted me in 2010, I kind of had my fill of people saying they were going to make a movie and then not do anything, so I figured he was another one of those guys. I was giving talks in New York, and I just told him, “Here’s where I’ll be.”

Pirooz Kalayeh: You said something like, “Well, if you want to do it then I guess you can do it.” That was it. But, I also wasn’t approaching him to do a movie of the book. I just wanted to follow him around and do a documentary about him. I read Hardcore Zen. Then I read Sit Down and Shut Up and Zen Wrapped in Karma Dipped in Chocolate, and Sex, Sin, and Zen had just come out at that point. I was just interested in what he had to offer. I thought it was fresh, new, innovative, and different. I was also curious as a spiritual seeker myself. I’m always looking for the answer to “What is truth?” in spirituality, because I feel like, for myself, it’s been difficult to wade through what’s real and what’s not real. I’m always looking. So, I started following Brad to find that out. And that’s basically what the documentary is.

Brad: I thought the idea of doing a film was interesting because I wrote for a film company (Tsuburaya Productions). I’ve been interested in film for a long time, and I thought that sounded like an interesting idea, and then I was just impressed that he would actually do it. This is the thing that constantly impresses me about Pirooz: he doesn’t just talk about these things; he actually goes out and makes them.

How long did it take to film?

Brad: It went on for like three years, and we were still filming things into last year that ended up towards the end of the film. There are some fairly recent things that Pirooz filmed like a month before he edited it, but we’d already done most of it by the time 2013 started.

Pirooz: Yeah. Basically, the skeleton of the film was done, and a lot of its meat was there, but there were a couple times I wanted to film something else.

So the main idea driving the project was to get a better sense of Brad’s work and what kind of person he is, and you felt it was important to get that out there so other people could realize it as well?

Pirooz: Yeah, I wanted to sort of put Brad out there. It seems like that’s what I gravitate towards. I like finding these artists and people who are on the periphery and then sort of give them a platform where they are going to be more visible. That was the same thing for Tao Lin and Shoplifting from American Apparel, that’s what I was hoping to do with Noah Cicero’s book The Human War, and then with Brad’s piece, too.

Brad: I’ve carved out this sort of miniature niche in the world of spirituality, but I realize I don’t fit the stereotype. I’m not interested in it as a thing like a hat that I wear that says in neon letters, “I’m spiritual.” But, I am interested in the practice, so it’s a really different approach. It’s just that’s what Buddhism is. It’s like talking about something as opposed to doing it. There’s a huge difference, and I think a lot of people don’t understand that Buddhism is a practice. It’s something you do. They’re sort of used to philosophies that you read and you sort of take in, and then you can sort of repeat in your own words what the book said. But there’s also a practice attached to this one, and if you’re not doing the practice, it doesn’t really matter if you can repeat what the book said. There are a lot of famous teachers from the Zen lineage who didn’t have any particular book knowledge of Buddhism, but they became very well known teachers because they practiced it. So, the idea of Buddhist practice is not that you receive the wisdom from a book, but that the wisdom is already present and you sit with it until you experience it for yourself. And if you experience it for yourself, you don’t need to read any books about it, because the books are just written by people who had experienced something themselves and were able to write it.

This reminds me of a scene in the film when a distinction is made between true Buddhism and what you refer to in your writing as “institutional Buddhist muck.” So is that kind of the idea here? The difference between people who are just reading about Buddhism and aren’t actually practicing, and those who are?

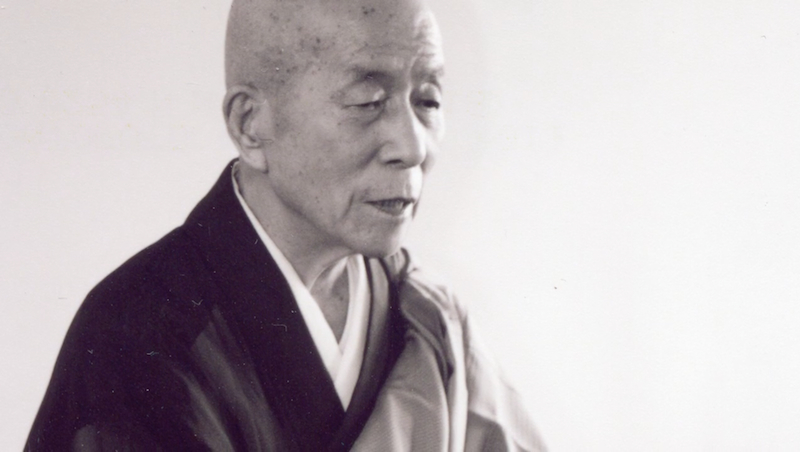

Brad: I mean, there are Buddhist institutions and they exist for a certain purpose, and they’re supposed to foster a practice. And, occasionally, they get much more interested in preserving the institution itself and lose sight of the reason they exist in the first place. They want to keep their buildings, titles, institutional power, positions, and rank within the institution. That’s what I’m talking about with institutions. Nishijima would talk about “true Buddhism,” so I started using that more than I use it now. ((Brad studied under Gudo Nishijima Roshi while living in Japan.)) Because I realize it sounds weird, I try to avoid saying it anymore. But, “true Buddhism” would be Buddhism that’s involved in practicing Buddhism rather than just talking about it or using it as a kind of lifestyle enhancement thing. It’s actual practice by actual people. There’s not much more to it than that.

Do you think the institutional element also has something to do with social identity and being able to be part of something?

Brad: I have done most of my actual zazen (meditation) practice by myself. I get up in the morning and sit, and this is what I do every day. That’s what we did this morning in the hotel room. But, there is sort of a social element to it that’s considered to be important, which is also why it’s considered to be very important within Buddhism to have a teacher. This is emphasized in all forms of Buddhism, not just Zen: you have to have a teacher. You don’t do this alone. The reason is that you kind of need to check yourself, and you need someone to do that for you. It’s easy by yourself to go wrong, to believe your own hype.

And Nishijima was especially influential in this regard, too, right?

Brad: There were points in my practice where I don’t know what would have happened if things were different. But, in retrospect, it seems to me that if I hadn’t had Nishijima around, I could have gone way off the deep end. I don’t think I would have been Charles Manson or anything, but I might have been one of those guys who’s like, “I found the answer. Come to me and learn the Great Truth.” Because I really thought, “Okay, this is it. I really got the whole thing down,” until this little old man comes and says, “You don’t understand anything,” and I go, “Yeah, I do. I understand everything.” Then, I started thinking, “Well, why am I worried about this little old man’s opinion if I know everything? Why would I be concerned about his opinion?” I had to be honest with myself and say, “I must not know everything if I’m worried about his opinion.”

This reality check, and making sure you don’t get too full of yourself, reminds me of the “ordinary guy” motif we see in the film, and the importance placed on understanding that the Buddha was just this ordinary guy who knew he had problems. Why is it so important to keep this “ordinary guy” motif in mind throughout your practice?

Brad: I mean, it’s in the movie, and I’m glad it’s in the movie, because it sort of spontaneously came out in one of the conversations that got taped. I suddenly kind of put two and two together, and went, “You know, this idea of Buddha being an ordinary guy isn’t just something. It isn’t just this sort of interesting sidelight to the story – it is the story.” If you start to regard Buddha as something other than an ordinary person, then it wrecks the whole thing. Then it becomes, “Oh, he did it, but I can’t do it.” Then you don’t do the practice. You don’t do the work yourself. So, yeah, I think that sense of being ordinary is crucial to the practice. It’s fine to have reverence or think things are holy or special, but once you elevate them to that other level, then you can’t do it. You can’t aspire to be like that.

Would you describe “enlightenment” in a similar sort of way?

Brad: A friend of mine was saying the other day that she felt like enlightenment is often conceived of as something like a finishing line. Then you cross that finishing line and you’re done. Enlightenment. There you go –

Pirooz: – the “end zone” mentality –

Brad: – then you check that off your list. And in my past, I’ve had that idea about it too – that it was something that happens, and then you finish and check that off your list and go on to whatever is next. But, there are experiences that people who meditate for a long time have, and often in the literature these experiences get names like “enlightenment,” “kenshō,” or “satori.” I believe that for most people who are pretty serious about meditation practice, if they work at it long enough, something like this will happen. It’s something that almost always happens if you’re serious and sincere about it. Once that happens, there’s a transformative experience and it’s not unimportant. It’s real. It really does happen, and it changes a person’s outlook on life forever. However, when you start calling that “enlightenment” and saying that it’s something that’s been accomplished, that’s where you go wrong.

Do you think it’s better to refer to these kinds of instances as, perhaps, “awakening experiences,” instead of trying to categorize them as Enlightenment with a capital “E”?

Brad: I don’t know what to call them, because I’ve been kind of struggling with that. Nishijima would sort of, on the one hand, deny enlightenment. Depending on how somebody asked about enlightenment, he would say, “Well, there’s no such thing.” And he wasn’t saying that these experiences don’t exist, but he was saying you’re misunderstanding the experience. Either you’re fantasizing about something you’ve never had and imagining something that doesn’t exist, or you’ve had an experience and you’re ascribing to it things that are not true about it – that it’s the completion of a task. He would talk about what he called “second enlightenment.” It’s a moment in which you understand what at first seemed obscure about Buddhist teachings. There’s a turning point for a lot of people when you just go, “Oh, I get that.” I didn’t know anything about Buddhism or Zen when I took a class about it at Kent State University. I wasn’t even that interested in Zen or Buddhism. I just took it as something that semester to sort of fill up the schedule. And then I heard the “Heart Sutra” and that phrase, “Form is emptiness, emptiness is form.” I didn’t know what it meant, but I thought, “That’s…that’s something. I don’t know what that is, but that’s something.” It was sort of this epiphany that launched me into Buddhism. I practiced enough and then got to the point where I was like, “Oh, I know what that means.” But then I find I can’t express it in better terms.

And maybe it’s actually better if you can’t really articulate those types of experiences, since doing so might turn them into some-thing that people strive to accomplish or figure out as well.

Brad: It might be, yeah, because everybody has got to figure it out for themselves. And that’s another sort of crucial thing, especially in Zen practice: you have to figure it out yourself. It’s not because your teacher is being mean and withholding information from you, because it can feel that way. I felt that way when I first started. I thought Tim was withholding something from me, or I thought if I could just pin Nishijima down and make him tell me, then we could just be done with all this screwing around. ((Tim McCarthy was Brad’s first Zen Buddhist teacher. The two of them met when Brad took his course on Zen Buddhism at Kent State University.))

So, in that sense, having discovered your own answers to these types of questions, would you say you have attained some sort of “enlightenment”?

Brad: Well, something changed for me in my life. I wrote about it in Hardcore Zen, and I decided to write about it again in the new book, There Is No God and He Is Always with You. I was walking across a little bridge over a tributary to the Sengawa River in Tokyo on my way to work, and at that moment everything shifted. But, what’s weird for me is I can’t pin down the date. I don’t even know what year it happened. Probably between 1997 and 2000. I think one of the reasons why it’s so hard to pin down a date on it is because it was something my teachers had talked about. They said you kind of stand outside of time. And I would hear phrases like that and go, “Stand outside of time? That’s stupid.” But it was an experience that encompassed all of time, which sounds ridiculous. And something like that is going to necessarily change you as a person. It’s going to change your outlook on life and a lot of things. But, it doesn’t fix everything.

Pirooz: You’re still just an ordinary guy.

Brad: Yeah. You’re still kind of maneuvering this life as whatever you are. And once something like that has happened, you can’t look at life the same way. People will say to me if I try to explain it, “Well, how do you know it wasn’t a hallucination?” And I reply, “It wasn’t a hallucination.” My favorite answer to that one is, “If you dropped a bowling ball on your foot, you would know that you dropped a bowling ball on your foot and nobody could tell you, ‘Oh, you hallucinated it, or maybe you just imagined the bowling ball.’” It’s that level of experience. Nobody’s going to convince me that didn’t happen.

And that comes up in the film, too. There’s this understanding that you’ve got a teacher who has experienced all these things, and nobody can really say otherwise, so it’s very difficult to argue with something that someone who’s been practicing for fifty years has experienced and is relaying. But, you do get the argumentation, and we see it in the film and throughout your writing.

Brad: Well, the thing is, my blog has become highly controversial. People comment and get very angry about things I say. We went through a lot of these comments, and sort of painstakingly attempted to track down some of the people who made them. We managed to find e-mail addresses for, I don’t know, a handful of them. Pirooz contacted them and said, “We’re making this movie. You are so interested in saying what’s wrong with Brad’s teaching, so come and say it in the movie.”

Pirooz: Anybody who’s making a documentary wants to make the most objective film, so you want the good and the bad, and that’s what makes something – having both sides of things. And everybody who had a negative thing to say just wouldn’t say anything. They just suddenly vanished and they never even replied to me, or they replied to me and said they’re not interested in the documentary. Only one person actually stayed, and he only said positive things. One of the things that he said at the end of the film was that Brad would be very popular after his death, and that sometimes people don’t recognize something until it’s gone. I almost feel like that’s one of the big things in the film, and a lot of the art that I’ve done is when I’ve noticed or seen something that was special and that people weren’t really noticing. There was something in me when I read that book, when I hung out with Brad, making this film, and I was like, “that’s fucking it.” I don’t know what it was, so in a sense, I was sort of with Brad like Brad was with Tim. It’s that same experience. I know it when I know it. I don’t want anybody to miss the next Van Gogh, I don’t want anybody to miss the next Nirvana, and I don’t want people to miss Brad Warner. We’re so lucky to have him. We are so lucky. And he’ll never let me say those kinds of things. Usually, he’ll be like, “Don’t ever say that again.” But, it’s the truth.

What about the physical altercation we see at one of the meetings in the film?

Brad: We gave James Roehl, who’s an actor and has been in a couple of Pirooz’s movies, lines that had been said on the Internet about me –

Pirooz: – because we had nobody who would actually say it, we were like, “We’ll do a staged fight.”

Brad: I do these meetings every Saturday in Santa Monica, and at one of the real meetings we had James, and there were a couple other ringers in the audience, but most of the people had no idea what was going on –

Pirooz: – so we had real reactions.

Brad: We had like four people in the audience who knew what was going on, including James and the film crew. We told the film crew something was going to happen, but we didn’t give them details about what it was. So, we just let James say this, and the idea was he was just going to get me so riled up that I’d jump him, and that’s what I did.

Pirooz: And maybe by showing this people will suddenly take the time to realize that making negative comments on blogs is unnecessary. It’s just unnecessary. It doesn’t do anything. And in fact, it might create frustrations on both sides when something else might be more productive.

It is a good depiction because nothing gets answered. He’s badgering you. You’re just trying to funnel his negativity away so you can get to what he’s asking, but you never do, because he’s not allowing you, so it just creates a hostile environment.

Pirooz: And that’s what it is on those blogs.

Brad: Yeah, that’s what it often becomes on the blog: this hostile environment where you can’t answer anything if somebody is not seriously asking the question. There’s kind of no point in answering it.

Pirooz: It’s almost like they approach it from an “us and them” mentality. As soon as you have that divider, there is no conversation anymore.

So what do you do, then? Let’s say that wasn’t a staged scenario, and something like that actually happened.

Brad: I have had people do that –

Pirooz: – the opening of the film.

Brad: Yeah, that was one. Unfortunately, the answer to that didn’t make it into the film, because it wasn’t absolutely necessary. I was invited to speak at this place in New York City, and it was difficult, but I was trying to say, “Okay. Well, this is the question you’re asking: ‘Why have you adopted the persona of a perpetual adolescent?’” That’s his question. And I said, “Well, what do you mean when you say ‘persona of a perpetual adolescent’? What makes you view me and think, ‘He’s being a perpetual adolescent’? Or somehow creating some kind of a persona that implies that it’s not real – that I’m really something else, but I’m just playing this role and dressing this way because I want to project something?” I just decide as a general rule that I try to figure out what the person is really asking and answer that question. I used to see Nishijima do the same thing. A lot of people would say, “Uh, Nishijima must be getting old or something, because we asked him a question and he didn’t answer the question that we asked.” For the first couple years I followed him, people would say this all the time, and I thought, “Oh, yeah. That’s true about him.” Then, after a while, I started paying more attention to what he was saying, and I realized he was always answering the person’s question. Every time. It’s just the people who were asking didn’t understand their own question. They think they’re asking about X and they’re using the words that apply to X, but they’re not asking X. They’re asking Q, and he was perceptive enough to notice that and answered what they were actually asking rather than this thing that they layered over it to the point where they didn’t even know what the question was.

Pirooz: That’s sort of what I’ve encountered with the films. As soon as you’re doing something that’s slightly alternative of what is expected, suddenly everybody wants to drag you through coals and hate you forever, and I don’t get that at all. It’s really bizarre to me. If I don’t make a film that’s exactly what you expect a film about a spiritual teacher to be, it’s because there is a purpose to it. It’s to say this is not a typical spiritual teacher, and if you start looking at the world like you need it to be like that then how are you actually going to get anything out of everybody else around you?

That seems to align with the Buddhist perspective, too – getting attached to these ideas and images of the Buddhist teacher or the filmmaker. Is one of your goals to dissolve these images and help people experience something more meaningful than what’s just being handed down generation after generation?

Pirooz: Aw, man. That’s what inspires me most of all. Just to have that experience – whether it’s in Zen, or whether it’s in art – that you do the unexpected and then suddenly you’re knocked into something that you didn’t expect, and you’re in like this open space to do something else. And that’s where I feel the most creative and inspired. That’s where I feel the most alive.

Do you have a favorite segment or scene in the film – perhaps one that you feel represents that creativity and inspiration the most?

Pirooz: My favorite part is probably the punk chapter, because I thought it really illustrated that whole concept. I liked how it went from punk to Brad talking, the images, and what was said. It just flowed so nice for me, and I thought it was just such a nicely done chapter. That was one of my favorite moments in the film, and probably the other one would be when I asked Brad about enlightenment. One girl was like, “He’s not enlightened,” and the other people were like, “Sure, why not?” I love the dichotomy, ya know? And it’s so cool to see all of Brad’s friends – like real, true friends – and they have all these different opinions about who he is.

Brad: I made some videos of Zero Defex, the band I’m in, and Pirooz used them in the film. I like seeing them on the big screen, since I actually made them on a laptop that was dying at the time. The laptop’s screen was really dim, so I had to edit without being able to see exactly what they were going to look like until I transferred them to another computer. To see them on the big screen is amazing. Some people who come and sit with me every Saturday kind of have this minor complaint to Pirooz that the movie doesn’t show enough of my serious side – it doesn’t show enough of “the teachings.” And I think that’s wrong. I think they’re missing a lot of it. One thing I like in the film is this thing I did called the Enlightenizer. It’s this little commercial. I kept wanting to try to do it with professional production values, but I could never get it done. So, one day I just decided to make a cartoon out of it and try to animate it. I think that comes across to a lot of people as like, “Oh, here’s a funny skit in the movie.” But it is actually a very serious thing that I’m trying to convey about how people approach this idea of “enlightenment.” They want the Enlightenizer. It’s like, “Get the Enlightenizer and it will get you enlightened while you drive, while you work, and while you operate heavy machinery.” And of course it’s bullshit, but to me that’s kind of the way people think. They think, “Okay, I want my enlightenment. Give me my enlightenment. I paid you. Give me my enlightenment. I gave you ten dollars for the meditation class…where’s my enlightenment?”

That certainly brings to mind the so-called “fast food” mentalities critics point out: “I want it fast, and I want it now.” Have you learned anything about yourselves throughout the filming of the documentary?

Brad: Yeah, I guess I have. It’s been interesting to see the film, because I tried to stay out of it a little bit. I wanted it to be Pirooz’s vision. But, I get this unique opportunity that most humans don’t. I get to see what I look like, and I guess in a way that’s instructive. I don’t usually get to see myself. So, seeing it on screen turns it into something else. I just see this other Brad Warner on the screen and it’s like, “Eh, am I that guy?”

Pirooz: Well, as an artist I learned how to edit a film better – how to make a stronger film – and I think that’s first and foremost for me. The other thing is probably just being around Brad and the teachings that he offers. I think the whole experience was just continually humbling in many different ways. There are just so many different things that I’ve learned. One of the things that I can cite immediately is when we were working on the Shoplifting film – I sort of connect the films together, because it seems like one big experience since they were filmed around the same time – I remember one of the actors was going around complaining about me, and I got really sad. We were eating and Brad looked at me and said, “Are you really sad? Don’t you realize that you’re the boss? You’re the director. People are always gonna talk shit about you.” And then I was just like, “Oh yeah, that’s true.” It was just that simple moment, and it really changed my filmmaking, because a lot of times I would be worried about what other people think of me – my actors or my crew. That was a great moment, and there are so many other moments. Probably the greatest thing I got was a friendship and teacher in Brad.

So, Brad. You note in the film that your initial interest in punk rock, and Zen Buddhism later on, had much to do with its questioning of authority and various conventions in order to feel something more authentic and real. Have you noticed any new bands or trends in contemporary music that you feel might be functioning in a similar way that punk rock did for you while growing up?

Brad: I don’t know. I imagine they exist. I do listen to a lot of things that are contemporary, but most of it’s so underground that nobody’s heard of it. I had this discussion about punk rock with some old punk rockers who said – and it was sort of this cliché for the old punk rockers – “The new punk rock is nothing like it used to be,” because a lot of the barriers have been broken down. So, older people who were into the punk rock in the beginning look at that and go, “Oh, yeah, these kids. They don’t know what it’s like.” And they don’t know that aspect of it, but they know other aspects of it, and I think for them, the bands that they’re listening to are just as relevant.

Pirooz: I think this can relate back to what Brad was saying about having spiritual teachers whose image or identity becomes institutionalized: they lose that sense of themselves, and it suddenly lacks a certain authenticity to it and becomes sort of watered down. The same thing happens in music. Once they get commercialized, they have to fight against that and they have to keep finding themselves in it. So, it’s really difficult to be an artist today and not be swallowed up by that.

Brad: I kind of feel like all the artists I admire most are those who never really got big.

Pirooz: For me, when I look around at bands, I’m always most inspired by the very local band that’s just trying to do it, because that’s when it’s the most real for me. And that’s when I get really excited.

I can detect some parallels here with Zen Buddhism and this “ordinary” quality we were talking about earlier: these bands staying raw, staying authentic…staying ordinary. But then you’re dealing with this awkward balance of trying to make sure it doesn’t become what you’ve been struggling to fight against this entire time yourself.

Brad: It reminds me of the idea of a “permanent revolution.” I’m not a big communist follower or anything, but communist thinkers had this idea that you had to have a permanent revolution. You can’t just have one revolution, and let the whole thing become entrenched. You have to keep revolutionizing the revolution.

So what’s in store for the future? Anything else in production?

Pirooz: Zombie Bounty Hunter M.D. is the big thing that we’re editing right now. It’s basically a satire – a warning – about how the Internet is changing our lives. The tagline of the film is: “Hits Are Everything.” And the philosophical question we’re dealing with is: “How far would you go to pay your rent with filming things on the Internet, and how bad can it get? Would you film your friend getting eaten by a zombie?” –

Brad: – because that’s what we’re doing. We’re filming people actually getting eaten by zombies, but we’re only concerned with how many hits it gets.

Pirooz: And Brad plays an exaggerated version of himself. We decide if we get a Buddhist priest to narrate the film, then it won’t seem as heartless that we’re filming these beings dying. And then he comes up with the whole Buddhist edict – that they’re already dead, so we aren’t actually harming them.

Brad: When I saw the script he’d written I thought, “Oh, this is really interesting,” because it seems to me kind of the way it’s going. Hopefully it won’t get as bad as what we portray in the film, but there’s this whole crew of people, including someone who’s supposed to be a spiritual leader, who are just totally co-opted by, “we’re gonna become big stars, and it doesn’t matter that we’re doing these horrible things, because it’s going to get hits.”

Pirooz: Gotta get the hits. In the movie, I ask, “Why are we doing this?” And Brad always replies, “For the hits.”

That sounds like a really interesting production! When will it be ready for screening?

Pirooz: Well, my guess is probably sometime in 2015. January 2015.

What about you, Brad?

Brad: I’m working on another book, but I don’t know exactly what it’s going to be. My tentative title is You Should Be Meditating, and the subtitle I have is What Meditation is and Why it Will Save the World. I’m really starting to believe that actual meditation may be necessary for normal human health. I always like to compare it to brushing your teeth, because there were centuries when people didn’t brush their teeth. They just let them rot out of their heads. And now everybody does it and we can’t imagine meeting people who don’t brush their teeth in the morning. I hope that there comes a time in the future when people will look back on the early twenty-first century and say, “Can you believe those people went out of the house without meditating in the morning? How could people interact? No wonder they had wars all the time. No wonder they had terrorism.” I really think people are going to look back on our era and criticize it in that way. And I think if you want to get past some of the horrible nastiness of pollution, environmental destruction, war, terrorism, rape, and murder, meditation is a necessary component for it, because you need the experience of seeing yourself really, really honestly. And if you see yourself really, really honestly, you find you can’t engage in those things anymore, because you go, “Ah, that’s stupid. I’m not going to do that, because that’s stupid.” I’ve only written like two or three chapters, so I’m still struggling with how it’s going to form.

So maybe sometime next year as well?

Brad: I hope I can get it done in a year. I’ve been pounding away at it.

Well, I certainly look forward to reading it!

Information about upcoming screenings of Brad Warner’s Hardcore Zen can be found here.

Good read here, and I found Brad & Pirooz to be pretty smart and thoughtful guys. Looking forward to their next project.

Jess O