It would be only a slight exaggeration to say that I live in a cold, damp, over-sized mailbox. For over a year I, along with my wife and six-year-old daughter, have rented a small, oddly shaped house nestled among fifteen acres of private land in Durham, New Hampshire. My acceptance of a position at the nearby university brought us from the densely populated suburbs of Manhattan to the Seacoast area of the state. Our landlord, a former NASA engineer, built the house with recycled materials and appliances, striving at every turn for energy efficiency.

“I always wanted to live in an airplane hangar,” he explained proudly as he led us toward a path that cut into the surrounding forest. Our lingering doubts about the unusual house vanished into crisp New England air as we stepped further into the playfully-named Ejarque National Forest and imagined our family’s new, year-round playground. Sixteen months later, our doubts about the house itself have returned, having suffered the minor annoyances of drafty doors, frozen pipes, dripping light fixtures, and a slippery-as-an-ice-rink driveway. But the forest never lost its draw, and in fact has become an unexpected source of insight for my teaching and research. My academic work, which touches on media, religion, and digital culture, is all the richer for having spent countless hours walking, sitting, and reflecting in the small oasis that we’ve come to call home.

While I generally prefer to leave my phone behind, I occasionally bring it with me to capture images and videos of this lightly-traveled piece of land. Metaphorically, however, many of these images capture key concepts behind my own evolving critique of digital culture: silence and solitude, presence and place, among others. The following reflections represent an early foray into an approach that I call contemplative media studies: the application of contemplative principles and practices to the critical analysis of media technologies, content, and institutions.

[nextpage title=”Silence/Listening”]

As I cycle or walk through the woods before and after class, I often find quiet spaces to rest and reflect on the questions that I or my students have raised. Tom Bruneau wrote that “an important and powerful manner of achieving silence” is “to go into naturalistic settings, into absolute privacy,” and then “to listen to and, then, become the natural music of water flowing.” ((Tom Bruneau, “An Ecology of Natural Mindlessness: Solitude, Silence, and Transcendental Consciousness,” Explorations in Media Ecology 10, no. 1-2 (2011): 69.)) The practice is uniquely effective in winter months, when the murmurs of a flowing stream are punctuated by heavy drops of melting snow falling from surrounding trees.

While such stillness is usually anathema in a classroom, it serves a special pedagogical purpose in the context of digital culture. Once per semester, I introduce my students to the work of composer John Cage, who is perhaps best known for his controversial piece 4’33”, in which the performer plays nothing and the audience, therefore, is burdened with the uncomfortable task of listening mindfully for the duration. It is a reflection on silence or, perhaps more accurately, the impossibility of it – a revelation that Cage experienced upon on entering an anechoic chamber. Expecting the absence of sound, he instead was overwhelmed by the high buzz of his own nervous system and the low hum of his blood circulation. Likewise my students hear voices from outside, footsteps in the hall, and the soft shifting-in-one’s-seat of bodies uncomfortable with silence itself. As evidenced by the video posted here, I often experience the same, as the sounds of a stream are displaced by a flying airplane.

A Buddhist, Cage came to understand that while there is no silence in the world, the possibility of silence nevertheless exists in our own capacity for equanimity in the face of what troubles the world has to offer. Not an idle observation, this instead is an insight into the nature of social transformation. Homosexual at a time when such identity was illegal or unspeakable, Cage’s provocative silence threw into sharp relief the limits of conventionality, both in the world of music and the world at large. Ironically, his conspicuous use of silence made him more – not less – an object of scrutiny for the powers that be. Yet as Jonathan Katz notes, it also provided a space within dominant culture for “other voices to be heard,” and, therefore, encouraged “a wholeness, a process of healing.” ((Jonathan Katz, “John Cage’s Queer Silence; Or, How to Avoid Making Matters Worse,” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 5, no. 2 (1999): 239-240.)) In this way, his work anticipates the distinction, drawn a few years later by Martin Luther King, Jr., between the negative peace of complacency and the positive peace of non-violent action.

Just as 4’33’’ marks the limits of commercial music (on what radio playlist could it possibly appear?), so too does it mark the limits of mass media at large. As Jacob Needleman suggests, the drive of commercialism has displaced the ideal of free speech with attention-seeking and idle chatter. ((Jacob Needleman, The American Soul: Rediscovering the Wisdom of the Founders (New York: J.P. Tarcher, 2002), 24-25.)) Whether on radio or online, silence is lost revenue: “dead air” in the radio era is echoed today in marketers’ disdain for social media or content sites that prize thoughtful readers over incessant clicks.

Today, Cage’s implicit commentary on sexual politics is arguably all the more relevant as click-driven content panders to masculine privilege and the basest sexual stereotypes. In 2012, for example, a popular but controversial Twitter feed at UNH boasted of knowing which campus women were looking for sex, based on their chosen articles of clothing on a given day. I argued in a brief interview with CBS Boston that the feed’s owner could not simply hide behind free speech claims, since this right is inseparable from the responsibility to listen mindfully. Indeed, when asked, students on campus expressed disgust and disappointment with the tenor of the feed. Hearteningly, in subsequent semesters several students have taken the charge of amplifying the unheard voices of young women and gay men who suffer the ill effects of revenge porn or cyberbullying.

Cage understood that the loudest, most incessant voices often perpetuate suffering through willful indifference to those who remain unheard. In this sense, learning to embrace silence and listen earnestly is a social and even political act, and one for which the solitude of the forest is a formidable – if not ironic – mentor.

[nextpage title=”Solitude and Loneliness”]

On returning from a whirlwind, five-state tour of our family and friends’ homes during Christmas vacation of 2012, I dashed into the knee-deep snow that covered the forest paths near our house. With the chatter of holiday dinners and A-my-name-is driving games still ringing in my ears, I stole into the woods, gazed up at the white-heavy branches, and sighed quietly, “My trees…” While I treasure our too-infrequent family visits, I know that as much as I love the company of friends, family, colleagues and students, I also love being alone. Yet I know that solitude is a dying art.

Roughly half a century ago theologian Paul Tillich wrote, “Today, more intensely than in preceding periods, man is so lonely that he cannot bear solitude. And he tries desperately to become a part of the crowd. Everything in our world supports him.” ((Paul Tillich, The Eternal Now (New York: Harcourt & Brace, 1963), 22. Quoted in Bruneau, “An Ecology of Natural Mindlessness,” 60.))

How prescient.

Connected devices have spawned a culture of availability in which we are available to everyone but ourselves, with a spate of sensational headlines decrying the psychic damage such gadgets have wrought. In this context, I should not be surprised when each semester many of my “digital native” students choose – with no prompting – to focus their semester-long projects on Internet and smart-phone addiction, crafting experiments in which their peers agree to give up their networked gadgets. The experiments typically end abruptly with students complaining that they wish their friends would stick it out a bit longer, if only to help complete the assignment.

But students’ enthusiasm for getting back online is betrayed by a clear ambivalence about whether it makes them happier. This is the paradox of connectivity-as-isolation captured on pop singer Morrissey’s aptly-titled album Maladjusted. In the ballad “Wide to Receive,” a loner who longs to “turn on, plug in” waits expectantly before a flickering screen, crooning, “and I’ve never felt quite so alone as I do right now.” It’s a sentiment echoed by many of my students, and one that points to a disjuncture between our embodied lives and the commodified friendships we unwittingly cultivate through social media. One wonders if King would count the allure of virtual friendship among those “things in our social system to which all of us ought to be maladjusted.” ((Martin Luther King, Jr., “The Current Crisis in Race Relations,” in A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings of Martin Luther King, Jr., ed. James Melvin Washington (California: Harper & Row Publishers, 1986), 89; emphasis added. Originally published 1958.))

At the end of the semester, as we discuss strategies and solutions for addressing the many concerns of digital culture, students understandably gravitate not toward institutional issues of policy and regulation, but toward personal solutions, such as adversarial design and information diets. Many respond most clearly to the simple suggestion to disconnect, if only for a moment. “Take a walk in the woods,” I suggest. “Meditate. Go jogging.”

These are not light-hearted suggestions. Sherry Turkle echoes a popular refrain in psychology in suggesting, “If you don’t teach your children to be alone, they’ll only always know how to be lonely.” To be able to accompany oneself, in solitude and silence, is an intensely contemplative skill that many are loathe even to attempt. Reflecting on our discussions, one student concluded her final paper with these thoughts:

We were asked in class if we are able to take time to focus only on ourselves and be comfortable with having “you” time, such as taking a walk in the woods or going for a run in silence. I was quick to say yes to the question initially because I run for exercise and it is one of the only times I am without anybody else. However, I had to remind myself that I cannot run without music from my iPhone. I have attempted to exercise without music and it feels unusually quiet and lonely. In my academic work, if there are not ear buds in my ears, there is a television show playing in the back ground to take my mind away from focusing on what is intended to be accomplished. I realized that every action I commit is supported through multi-tasking. I discovered that when I am away from other people I use multi-tasking as a coping mechanism so that I do not ever feel unaccompanied. For the first time in my life, I took into consideration that maybe I am scared to be fully isolated. ((Used by permission; emphasis added.))

Jung argued that many of our cultural pathologies stem from fear of our own unconscious thoughts – the vast “undiscovered self” that constitutes the subject of all authentic religious quest. ((C.G. Jung, The Undiscovered Self (New York: Signet, 2006). Originally published 1957.)) This is the presence that draws near in those moments of restful contemplation that our hand-held devices so efficiently push out of reach. Yet it’s in those moments of focused attention that we find an equanimity that bolsters our resistance to – and may ultimately transform – the web of distraction that surrounds us.

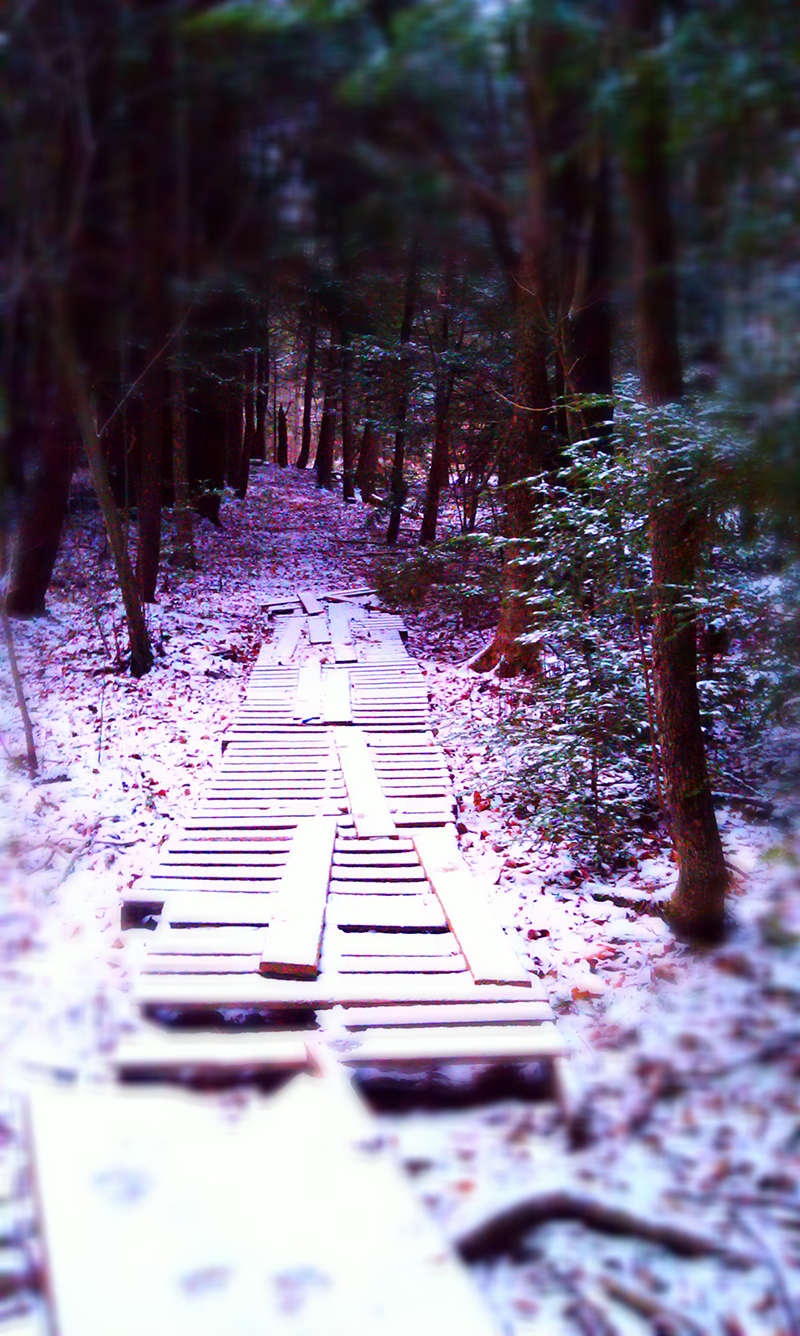

The urge to connect is strong, however, and I claim no immunity. A few weeks after we arrived home from our holiday travels, the deep snow melted, vanished, and was soon replaced by a new, lighter coat of white. This time, I took to the path with my smartphone in pocket. Gazing down a long stretch of flurry-covered wood pallets, I snapped a photo and posted it to Facebook with a caption that read, “If I take a walk in the woods and don’t upload a photo to Facebook, did it really happen?” The “likes” rolled in, and I felt a bit warmer inside.

[nextpage title=”Centers/Worlds”]

When exploring new terrain, a mindful hiker intuitively senses moments in the landscape either when senses are balanced – not too elevated, not too crowded in – or when senses peak in a meaningful way – a spectacular vista, an especially calming micro-climate. These are centers – spaces from which the four directions seem to originate. Such centers become focal points for restful focus on one’s next walk.

I’ve found several of these in our woods. One of these sits slightly higher in elevation than the surrounding paths, overlooking an oft-dry streambed and a pallet bridge that suggests movement and passage. In the warmer months, sunlight floods the ground and sparkles from the tree leaves. Such spaces call us to pause, and when we do, they aid in the process of reflection.

In The Sacred and the Profane, Mircea Eliade argues that human beings seek to reenact the cosmogony – the creation itself – in our personal and communal spaces. “It seems an inescapable conclusion,” he writes, “that the religious man sought to live as near as possible to the Center of the World.” ((Mircea Eliade, The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion (New York: Harcourt, Inc., 1987), 43. Originally published 1957.)) Echoing Jung’s argument that authentic practice places us in contact with the unconscious self, Eliade argues that the most sacred spaces are those in which earth, heaven, and the underworld are connected. When the daily process of world-building – relationships, communities, careers – becomes a burden, natural environments invigorate us by offering newly found centers that, through their stillness, invite and inspire us to build again, from the center.

If it is true, as Eliade suggests, that “every construction or fabrication has the cosmogony as paradigmatic model,” what shall we make of our attempts to create spaces, selves, and centers in cyberspace? ((Ibid., 45.)) In No Sense of Place, Joshua Meyrowitz describes how electronic media disrupts established boundaries between ages, genders, and races, causing shifts in our cultural landscape with far-reaching consequences. ((Joshua Meyrowitz, No Sense of Place: The Impact of Electronic Media on Social Behavior (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985).)) Some of these are positive: the blurring of subcultural borders can erode social pretensions of authority and difference and have an equalizing effect. As the sociologist Carl Couch notes, however, while electronic media may be “moving us toward a global village,” villagers “have never been particularly harmonious.” ((Carl Couch, Information Technologies and Social Orders (New York: Aldine de Gruyter, 1996), 249–250.)) Boundaries are blurred but re-drawn, often in imperceptible ways that re-entrench established power. In digital spaces, analog-era gatekeepers like newspaper editors are nudged aside by software engineers whose code regulates the structure of our online experiences and personas.

Digital spaces are alternately too structured and too unpredictable. Algorithms that aim to “personalize” our online experience may ensconce us in “filter bubbles” of familiar taste and unexamined prejudice. ((Eli Pariser, The Filter Bubble: What the Internet is Hiding from You (New York: Penguin Press, 2011).)) In cyberspace, where “code is law,” even the option of civil disobedience may vanish, as in the case of Second Life’s hard-wired restrictions against trespass. On the other hand, the ubiquity of code, and its ever-present malleability, create spaces that are as unstable as the shifting staircases that Harry Potter encounters at Hogwarts. Code is like sand shifting under our virtual feet. When Facebook decided to publicize users’ retail purchases, and later re-structured its default privacy settings to nudge users toward more public sharing, users understandably revolted. A class action suit shut down the former program. As Eliade notes, disruptions in the built structures of our lives cause a dreaded sense of return to primordial chaos. ((Eliade, 48.))

This lingering sense of unreality and instability in the digital realm may explain the rising interest in hobbies and practices that return us to our immediate physical space. Reflecting on recent trends toward do-it-yourself food-making like canning and butter-churning, food writer Bee Wilson suggests such trends may be “a response to the computer age.” “We’re just spending so much of our lives living in a sort-of virtual capacity, staring at things, that’s it very therapeutic to do things again,” Wilson told NPR recently. Journalist William Powers likewise argues that the desire to refocus offline may explain the widespread interest in yoga and meditation. ((William Powers, Hamlet’s BlackBerry: A Practical Philosophy for Building a Good Life in the Digital Age (New York: Harper, 2011), 63.))

Of course, such practices may treat the symptoms of virtual malaise without impacting the underlying disease. The social and economic necessity of our engagement with digital media underscores the importance of restructuring digital ecologies so they might serve users rather than treating them as mere means to an end. What may bring stability to such spaces is not the transparency of our personal lives to marketers, but the transparency of software code and data collection policies to citizens. This, in turn, requires cultural norms and political policies that understand journalism as a public good, and that see privacy not in terms of utilitarian cost/benefit analyses but as a basic right that underpins the authentic pursuit of human dignity. ((Robert Bodle, “Privacy and Participation in the Cloud: Ethical Implications of Google’s Privacy Practices and Public Communications,” in The Ethics of Emerging Media: Information, Social Norms, and New Media Technology, ed. Bruce E. Drushel and Kathleen German (New York: Continuum, 2011), 155-174.))

Such stability as a long-term goal may necessitate disruptions in the short term, such as those caused by Edward Snowden’s release of NSA surveillance documents. Indeed, in their letter nominating him for a Nobel Peace Prize, Norwegian politicians Baard Vegar Solhjell and Snorre Valen argue that Snowden’s disclosures may ultimately have “contributed to a more stable and peaceful world order.”

Reflecting on the photo of that spot in our woods by the dried streambed, I recall the times that I stood in that space, quietly staring at the barely-visible but well-trod pallet bridge in the distance. While restful in appearance, a bridge nevertheless symbolizes the inevitability of passage and movement from one world to another. As exemplified by the images from the 1965 civil rights march on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Alabama, in moments of civic action a space of passage can – paradoxically – become center in itself, as resistance to political power becomes an act of recreating the social world. These images suggest a lesson for practitioners of contemplative practices: namely, that to practice with integrity leads not to disengagement or detachment, but renewed engagement with greater wisdom. At some point, the moment of stillness we achieve will evaporate, as we are jarred back into motion by some obligation or another. This is as it should be: ultimately, a center is not a place where you remain, but a capacity you carry with you as you move through a world that surely will, and must, change.

[nextpage title=”Persistence and Decay”]

During the heaviest snowfalls, even the strongest trees are vulnerable. The weight of wet, sticky snow bears down on large branches and, with the help of gusty winds, causes the structure to collapse. Walking along the forest paths in the spring, we see newly fallen branches and trunks alongside those that have come before. Older fallen limbs are less striking, but reveal the underlying message of a sustainable ecology: that which has served its useful life gives itself up in service of new life. A fallen branch is a buffet of decay as animals, insects, fungi, and moss pick and choose from the offerings. But what if these giants refused to submit themselves to the ecosystems that surround them, stubborn and stingy as the creatures that Dorothy, Tin Man, and Scarecrow encounter in the forest of Fighting Trees?

As media and policy critics note, corporate giants of the film, record, and tech industries have likewise held the fruits of artistic labor close to their chests, under the protective shield of ever-more-restrictive copyright and intellectual property laws. It is an issue highlighted in a meme that spread through social media last New Year’s day under the title, “What Could Have entered the public domain on January 1, 2014?” The answer: Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, Dr. Seuss’s The Cat in the Hat, and – perhaps most ironically, given her role in inspiring the very policies that exacerbate corporate overreach – Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged. Had copyright terms not been extended through industry pressure and Congressional acquiescence, these works would have been released as “free as the air to common use.” Instead, we will have to wait until 2053 – assuming that Ray Kurzweil’s much-anticipated Singularity doesn’t render all such debates obsolete.

The zeal with which commercial entities tighten their stranglehold on art and culture is reminiscent of a well-known Zen story called the Black-Nosed Buddha:

A nun who was searching for enlightenment made a statue of Buddha and covered it with gold leaf. Wherever she went she carried this golden Buddha with her.

Years passed and, still carrying her Buddha, the nun came to live in a small temple in a country where there were many Buddhas, each one with its own particular shrine.

The nun wished to burn incense before her golden Buddha. Not liking the idea of the perfume straying to others, she devised a funnel through which the smoke would ascend only to her statue. This blackened the nose of the golden Buddha, making it especially ugly. ((Paul Reps and Nyogen Senzaki, ed. Zen Flesh, Zen Bones: A Collection of Zen and Pre-Zen Writings (Massachusetts: Tuttle Publishing, 1998), 64.))

There have, in fact, been numerous instances where commercial organizations have blackened their noses, so to speak, through egregious attacks on unwitting violators of unreasonable copyright policies. In the mid-1990s, the songwriting organization ASCAP issued a licensing order forbidding camps like the Girl Scouts from singing “This Land is Our Land.” ((David Bollier, Brand Name Bullies: The Quest to Own and Control Culture (New Jersey: J. Wiley, 2005), 14-16.)) The response was furious. “We got a big black eye from this,” one ASCAP official admitted. More recently, Warner Brothers sent cease-and-desist letters to young authors who, to the surprise and delight of their English teachers, had begun drafting their own creative fiction based on the Harry Potter novels. Fans, including one articulate teen named Heather Lawver, resisted and forced the company to revisit its policies, however tepidly. ((Henry Jenkins, Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide (New York: New York University Press, 2006), 186-188.)) It was another black eye – or nose – for another industry organization.

Despite these newsworthy incidents, the trend toward increased copyright and intellectual property control continues, catalyzed by the trend toward convergent networked technologies. While file-sharing networks have introduced a challenge, they have not precipitated the downfall of industry copyright regimes. On the contrary, as Lawrence Lessig argues in Code 2.0 copyright may be “about to be perfected” through the development of digital rights management (DRM) technologies and industry-friendly policies. On a broader scale, companies like Apple, Facebook, and Google have moved toward a “walled garden” approach that locks user data within “tethered” devices and proprietary data clouds. ((Robert McChesney, Digital Disconnect: How Capitalism is Turning the Internet Against Democracy (New York: The New Press, 2013), 135-136.)) Led by the self-identified Buddhist Steve Jobs, Apple edged toward such closed systems early on, with others following closely behind. In the networked era, in other words, the pipe that funnels the smoke to the black-nosed Buddha is patented and wired for efficiency.

While the ironies stemming from Silicon Valley’s appropriations of Buddhist principles are many, in this context an off-the-cuff quip from Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg stands out. In response to the backlash against the company’s decision to change users’ default privacy settings to “public,” Zuckerberg stressed the importance for his employees to “always keep a beginner’s mind” by asking, “what would we do if we were starting the company now.” The irony in this case is that those who truly keep a “beginner’s mind” with regard to digital media argue that our best bet for harnessing its democratic potential is to wrestle it from the strong arms of corporate capital altogether. This is an uphill battle, of course. But if, as Robert McChesney argues, we are at a critical juncture in our technological and political history, then the “last domino to fall” may be the emergence of widespread social unrest stemming from the economic disruptions to which tech monopolies have contributed. ((Ibid., 67-68. On the issue of social disruption see also Thomas B. Edsall’s New York Times review of Thomas Piketty’s recently published Capital in the Twenty-First Century.)) Thus, the fate of Silicon Valley may resemble those giants of the forest who, stubborn in their refusal to serve any but themselves, ultimately succumb to the cumulative weight of each tiny flake in the cold blizzard winds.

[nextpage title=”Presence”]

On an infrequent visit to the nearby Fox Run shopping mall, I came across a backlit billboard featuring a public service ad from the Ad Council’s Discover the Forest campaign. The ad depicts two images: one of a young boy sitting cross-legged while staring at a hand-held screen, and the other of the same boy sitting in a forest, intently studying a fern that he holds in his hands. The caption reads simply, “Unplug.”

It is, of course, unsurprising that the rare message imploring children to step away from networked screens and into the natural environment is funded by a non-profit public interest organization. Typical rhetoric from technology leaders and marketing campaigns touts the benign, if not salvific, powers of connectivity. A commercial from Verizon’s “Revolve” campaign, for example, depicts a young family surrounded by a glowing ring of screens that descends from the sky and offers – apparently – untold joys. Such messages ask us to believe that to be connected is to witness the presence of that which truly deserves our attention.

And what of the fern held in the boy’s hand? Sherry Turkle observes that connectivity often calls us away from the embodied present, even in spectacular settings. We walk the dunes, but we are not fully present to their beauty. Echoing Verizon’s marketing call to “share everything,” the scene becomes fodder for a future upload or update. More wryly, comedian John Oliver wonders aloud what scenes might have unfolded had witnesses of the crucifixion been equipped with video-capturing smart phones. In each case, the allure of connectivity violates what Oliver calls the “dignity” and “poetry” of otherwise sacred moments.

In natural settings, solitude becomes paradoxical when one becomes comfortable enough in one’s aloneness to realize the commanding presence of life that surrounds us. We believe we are alone amid the trees until we realize the imposing presence of the trees themselves. As Jewish theologian Martin Buber describes, in such moments the “it” becomes a “Thou”:

It can, however, also come about, if I have both will and grace, that in considering the tree I become bound up in relation to it. The tree is now no longer it. I have been seized by the power of exclusiveness. ((Martin Buber, I and Thou, 2nd edition (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1958), 7.))

To be seized in this this way requires that we extricate ourselves, at least for a time, from the pressing demands of networked devices. This explains some recent, eloquent calls for a return to the institution of the Sabbath—the intentional respite from both commerce and state power. Jewish theologian Michael Fishbane explains that “On the Sabbath, the practical benefits of technology are laid aside, and one tries to stand in the cycle of natural time, without manipulation or interference.” ((Michael Fishbane, Sacred Attunement: A Jewish Theology (Illinois: Chicago University Press, 2008), 125-127. Quoted in Walter Brueggemann, Sabbath as Resistance: Saying No to the Culture of Now (Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press, 2014), xi.)) As David Levy and Walter Brueggemann argue, it is a practice that may serve not merely as a stress reliever but as a form of political and social resistance.

For the past sixteen months, the fifteen acres of woods surrounding our oddly-shaped home have served as a sanctuary, and my brief but frequent meditations among the trees have served as a Sabbath of sorts. Now, rounding the corner on my fortieth birthday, my family and I are preparing to move out of our rented home to a house that we will own. While just a few minutes away, the new space is tucked in a family neighborhood close to the center of town, seemingly far from the solitude of the forest.

I will miss these woods. But they are a luxury to which many have no access. It is fitting that we should move away from the forest, if only to remember that while its sanctuary deepens our capacity to appreciate the commanding presence of life, our most pressing obligation is to turn to family, neighbors, friends, and enemies and resolve to recognize in each the eternal Thou. That is an obligation from which we ought not be distracted, and which we realize most deeply when eye meets eye against the soft beating of an analog heart.