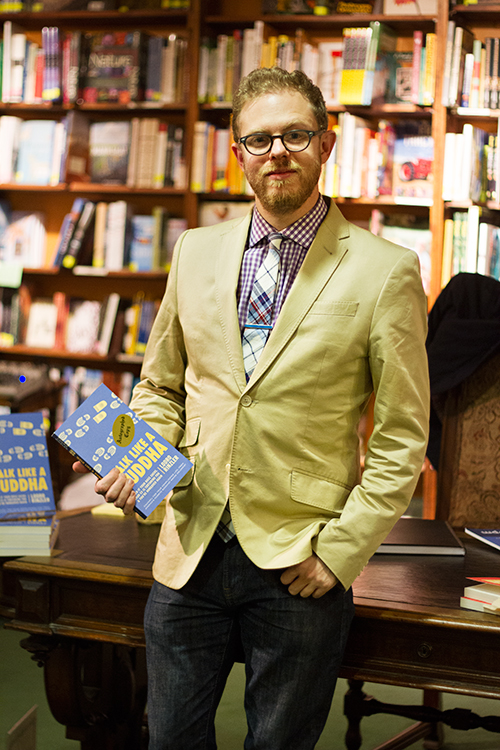

Buddhist teacher and author Lodro Rinzler sat down with Nomos Journal’s Seth M. Walker earlier this month to discuss the application of Buddhist teachings in the contemporary world. The Tattered Covered Book Store in Denver, Colorado, was just one stop along Lodro’s recent book tour following the release of Walk Like a Buddha: Even if Your Boss Sucks, Your Ex is Torturing You & You’re Hungover Again.

Hi, Lodro. Can you tell us a little bit about yourself, Buddhist lineage, and background as a teacher?

Sure. I was raised within the Shambhala Buddhist lineage, and it was brought over by a Tibetan Buddhist teacher in the late sixties: Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche. As he encountered the West, he realized that his teachings on meditation were really applicable to people’s lives and that individuals didn’t necessarily need to become monastics to become practitioners. The main thing that he emphasized was meditation as a way to be in the world – to actually breed mindfulness and compassion so that people could bring that out and help others. My parents started studying under him in their twenties and early thirties. After I was born, I met him and started doing meditation retreats pretty early on – when I was about eleven. When I was seventeen, my parents knocked on my bedroom door and said, “You know what would make for a really good college essay? If you ran off to the monastery in Nova Scotia for a summer.” I didn’t have anything else going on, so I said, “Why not?” and went out to this beautiful abbey – Gampo Abbey – shaved my head, took the robes – the whole nine yards – and spent the summer out there. When I came back, it sort of backfired on me because it did make for a good college essay, but when I got to college – at Wesleyan University – all I wanted to do was meditate and study Buddhism. That’s all I did. I started a Buddhist meditation group there, and then went on to continue to teach in various places: Shambhala centers, other meditation centers, universities, and all sorts of places.

Was it difficult to balance those developing aspects of your spiritual path with your life as a college student?

Even though I did grow up within a Buddhist tradition, I was exposed to a lot of alcohol, casual dating, and things like that when I went to college. And yet, I was a hardcore Buddhist, and I was trying to practice at least an hour a day. It took a long time for me to actually figure out my own Middle Way between these various roots of overindulgence in alcohol, drugs, women, and whatever it might be, and then locking myself up for days at a time and trying to be a solitary meditator. Then, after a couple years out of college, I figured out that I wasn’t alone in all that. There were other people who were also trying to do that. They were also trying to live a spiritual life. They were also trying to meditate. They were trying to bridge this gap between meditation and the rest of being young, and I tried to write about that. I ultimately didn’t have a lot to say at that point, so my friends and I came up with this idea for a column that we would do for his blog called: “What Would Sid Do?” Sid being short for Siddhartha – not because I mean any disrespect, of course, but because I figured they did have nicknames 2600 years ago and maybe that was his. But, he was a twenty- or thirty-something who was confused by his spiritual path and then ultimately discovered how to actually wake up in a big way through the meditation practice that’s introduced in these books. We can follow in his footsteps – walk like a Buddha – and apply this to our everyday lives.

Is that what eventually led to you writing your first book, The Buddha Walks into a Bar?

Yeah, I mean, both books are looking at how we actually bridge that gap that I was just talking about: how do we actually start to become present on the meditation cushion so that we can actually be present throughout the rest of our life? And both of them include things like showing up at work or school, social action, romantic entanglements, going out with friends, all of that. The first book is my first child. I love it, but I was really cramming a lot in there.

What would you say separates it from Walk Like a Buddha?

Walk Like a Buddha is fifty questions that people asked me. It’s the dialogue book. It’s the book that came after me saying, “Hey here’s an idea, what if we brought our meditation practice to the bar with us? What if we brought it to online dating? What if we brought it to work?” After that, I toured to thirty-six cities, and people just showed up and had the best questions about all these sorts of topics. We’d have a discussion, and I realized that this was something that people wanted to talk about. So, this book is a dialogue between me and various people who wrote to me, showed up at events like tonight, and asked these questions, or they found me on Facebook or Twitter, or whatever it might be. They all asked these questions and it was fun for me to write because I was actually writing it in response to other people. So, it’s not just me in this book; it’s actually sort of a communal book. That’s one of the big differences. To answer your question probably a little bit more open-heartedly, I would say I’m also different. While I was working on The Buddha Walks into a Bar, I had a very stable 9-5 job, I was engaged to be married, I had a really stable family and social life, and then all of that fell apart right after the book came out: my fiancée and I parted ways; I was cut from my job; one of my best friends died; and my dad died. I went out to Ohio to see where my friend had been working on the Obama campaign, and all of my friends sort of pushed me to go out there and work on it in his memory. I put all of my stuff into storage in South Street Seaport before leaving, only to have Hurricane Sandy come in and wash it all away. It felt like every time I thought nothing worse could happen, something else happened. After all of that, I sat down and wrote Walk Like a Buddha. So, I think I’m different. I think I’ve seen suffering in a different light. I think I’ve been sort of put through the ringer in a good way. In terms of my own spiritual practices, my own faith being tested, and the teachings I talk about…I think it’s made it a stronger book as a result.

You mention a practice Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche referred to as “mindful drinking” in both books, and explore the potential for “right drinking” more generally in the second chapter of Walk Like a Buddha: “Play Like a Buddha.” Can you explain how going out and having a few drinks can be approached with mindfulness, especially since many outspoken and prominent Buddhist teachers are very adamant about the negative aspects and detrimental qualities associated with alcohol consumption?

Within my lineage, and as represented by Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche, my teacher, it’s okay to have a glass of wine here and there. And, I make it very clear in the second book that I’m not saying go binge drink and call it meditation. That’s not what I’m saying. It’s a little bit like when I talk with friends who work in high schools and they say: “Well, the kids are going to have sex anyway, so we might as well talk to them about it, and try to get them to be safe.” That’s sort of how I feel about this. If I went down to this event today and asked, “Who here has meditated before?” Maybe half or three quarters of the people might raise their hand. But if I asked, “Who’s been to a bar before?” Every hand would go up. So, if people are going to go out and do this anyway – if they’re going to go out and drink – should they sit there and feel ashamed? No. They should be able to meditate. And, ideally, they should be able to be more present with their situations when they go out so they don’t lose their head as often and are less likely to cause harm. One of the things that the Dalai Lama has said is, “In all things, don’t cause harm.” Our purpose here is to be helpful, and if you can’t be helpful, don’t cause harm. We can have that attitude when we go out on a Friday night. And if we’re going to be at a bar on a Friday night, do we have to say, “I’m doing that everywhere else but not here”? No. I don’t think so. I think we can still show up in that way. We shouldn’t have to say, “I’m going to go be a meditator and a spiritual person, except in these sorts of situations.” It should be everywhere.

In the next chapter, “Getting it on Like a Buddha,” you address the topics of casual sex, multiple partners, open relationships, and masturbation, and indicate that although these things can often carry negative connotations, they can also be viewed as beneficial and sacred acts that can help us develop healthy, interpersonal relationships. How can we approach these particular topics and behaviors and appreciate them as positive and beneficial, as opposed to things we should be shaming or hiding?

I feel like there are some people who are like, “Oh, this is a great book for me because I’m doing these sorts of things,” and some people who are like, “How dare you even talk about these things?” I think there are times when people cling to certain aspects of the Buddha’s teachings and don’t look at how they’re actually being applied to people’s lives. The whole point of these books is not to say, “No, you can’t do this,” or, “Here’s why you can’t do this.” When the Buddha opened to his first students 2600 years ago, he didn’t say, “You need to do these sorts of things: you can’t masturbate, you have to eat these sorts of things on Sunday, and you have to go here on these sorts of days.” The first thing he said was, “Come see for yourself.” Living in line with these teachings is a very personal journey. There are no set commandments for us in a traditional sense. There are certainly rules for monastics, but for us lay practitioners, if we’re going to go out and we’re going to date, it could come down to this question we were talking about before: “Am I hurting people or am I helping people?” With casual sex, and things like that, I do feel it’s a little bit like taking out a chainsaw, because if you don’t know what you’re doing with it, you’re just going to end up hurting people. If you’re just like, “This is fun, it’s a chainsaw!” or, “This is fun, it’s an open relationship! It’s casual sex!” you’re probably going to end up hurting people. But, if you actually know what you’re doing and are in communication about what’s happening and why you’re doing it, then that might actually be a helpful experience. There are times when flings, open relationships, or one night stands could actually be beneficial for both parties. It’s probably rare, but I think it’s possible. I’m not going to tell anyone that they’re a bad Buddhist for trying to do so.

It seems like what you’re indicating in the book when answering these kinds of questions is that intention plays a large role as well – the “why” behind the “what,” so to speak – and that seems to be the indicator of whether or not something can be positive and beneficial, or if it’s negative and should be avoided.

That’s exactly it. When I’m teaching a workshop, or at a university, one of the main things I address is intention and discovering what you want to do and how you can live in line with that. For people who want to talk about relationships, it’s the same thing. Why do I feel like I need to be in a long-term relationship? Is it because I’m lonely? Is it because I just broke up with somebody and I’m trying to cover over the pain of my broken heart? Is it because I just met someone and I feel a real connection and I’m not sure where it’s going, but I’ll explore it? As you said, the “why” behind the “what” is the most important part of all of this.

Why do you think this perspective – embracing certain, seemingly negative behaviors or activities as being potentially positive and beneficial – might be met with some reservations, especially in the U.S.?

I think it’s very easy to cling to a religion. I was on NPR the other day, and someone called in and asked, “What is this whole thing? Is it a religion; is it a philosophy; is it a way of life?” And, the thing that came to my mind was, “It’s a practice.” Yeah, there are teachings, and there’s a way-of-life aspect, but a way of life is a practice. Meditation is a practice. Buddhist practices try to help you become more awake so you can be awake in the rest of your life. So, how that manifests is actually going to have to be in line with what’s going on in society today and what’s going on in your life today. There’s no way that the Buddha could have predicted that we’d have online dating, Facebook, or any of the things that we currently have. He didn’t give sutras for Facebook, right? So, it’s up to us to figure out how to deal with it. There are people out there, and it’s perfectly natural because this is how we work, who want to solidify everything and say, “All right, here’s the right way to be a Buddhist, and if you don’t do what I do, you’re wrong and you’re not doing it right. You’re bad.” This is how wars get started. This is basic disrespect for someone else’s experience: I have my tight religious beliefs and you have your tight religious beliefs, and then they don’t mesh so we have to fight about it. But, I think if we start to think about it more as a practice and a way that we can actually be in the world, then I think we’ll actually wake up and be more successful at following in the footsteps of the Buddha. I also think that’s happening already: for every traditionalist out there, there are ten people who are interested in what Google is doing, for example, and their “Search Inside Yourself” leadership training. It’s sort of infiltrating our society in a different way, for better or worse. There’s meditation that’s being offered as a practical tool without much of the teachings surrounding it, and I sort of have mixed feelings about that. The practice is wonderful in and of itself, but it needs the support of the teachings so we know what we are actually discovering when we sit down to meditate, which is that we’re basically awake. There’s no real difference between the Buddha and us in that way. It’s not like he was a god or some super spiritual being who came down to save us. He was a person who woke up and we can follow in that.

In both books, you note how Buddhism has traveled to different parts of the world and has existed in different historical contexts, and that we’ve got this constant adaptation to the teachings taking place. It sounds like what you’re saying right now with these remarks – and in the books – is that we should attempt to cut through some of the more antiquated theological stances – of what became various Buddh-isms – and instead keep our focus on what the Buddha was teaching as a universal and constantly evolving message.

Yeah, and I’ll give a very specific example in this regard. So, many years ago, in the mid-late nineties, the Dalai Lama sort of put his foot in his mouth when he quoted this very traditional text by Tsongkhapa, an eleventh century teacher in the Tibetan tradition. He was asked how he feels about homosexuality when he was visiting the West. The thing that is traditionally said about this, he said, is that sexual misconduct is defined as any sort of anal sex, masturbation, or sex during the day. So, basically, it wasn’t just offensive to homosexuals; it was offensive to anyone who wants to wake up and have sex with their lover. It’s really, for our purposes in the West, an outdated text. Ultimately, he came back and said, “This is not what we need to stick to here in the West. We’re going to look at these traditional teachings that have been set in stone, and what we need in order to change these things is communal dialogue.” I love that, because this is what we’re trying to do here. This is why I travel. This is why I write books for dialogue. It’s like we’re starting to have a conversation around what this means for it to actually look like in the West.

Given all of the distractions that bombard us each day, which seem to be steadily increasing with developments in technology, social media, etc., how do you see meditation and mindfulness practice being affected?

I guess this is why I worry about mindfulness and meditation being divorced from Buddhism overall, because it’s hard, and I think people want to make it easy and make it easily commodified. I was visiting my sister recently and she told me her friend had an idea for a ten-minute, easy, drop-in meditation center. Her friend hadn’t really done much meditation, but she said, “Ya know, that way it’d make it really easy for people.” And it’s not easy. It’s not an easy thing to do. It’s frustrating. It’s hard. Sometimes you’re bored. Sometimes you want to leap off the cushion even though you have to sit for another seven minutes and it’s only been three so far. We’ve just gotten really used to instant gratification. This culture of instant gratification just blows my mind. And meditation is not that. Meditation is more like, “Uhhhh, I’ve been doing this for days, or weeks, or months, and I’m not exactly sure why it’s not helping me.” But, something very subtle might be taking place. It’s not always so obvious that we feel propelled down the path and want to do it 24/7. So, I think that’s going to be a major obstacle for people, long-term: the fact that we have to commit to it and sink into it before we actually see results.

How does the ability to “multitask,” which is often praised as a beneficial talent, relate to this? Does it inherently impede one’s ability to be completely mindful of what’s taking place?

It does. Yeah. I feel like we have a sense of productivity that’s gotten pretty skewed – like we can half-ass a bunch of things and somehow get by, as opposed to just committing ourselves to something. This is not to say that I myself don’t occasionally open up my phone to see if there’s an email while I’m watching TV, because things like that happen. But, I’ve started to avoid that. There’s this beautiful segment with comedian Louis CK on Conan. He said he wasn’t going to get cellphones for his kids because at some point it’s like we just need to actually be alone with ourselves for a little bit and not have some product or object that allows us to get distracted. Can we actually just be with what’s going on, even if what’s going on is boring, or lonely, or heartbreaking? Can we actually show up for both the pleasurable and the painful aspects of our life? There’s this beautiful line in Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s poem “Timely Rain” that reads, “In the garden of gentle sanity, may you be bombarded by coconuts of wakefulness.” I love that, because it’s like we’re going about our life, and then all of sudden we just get knocked – not with something like an acorn, but by a coconut – to our knees with something painful. It’s not that it’ll make you curl up in a ball and not see anyone, or force you to try to drink your sorrows away. It’s the coconut of wakefulness. It’s indicative of an actual opportunity to go down the spiritual path in a more wakeful way.

In the introduction to Walk Like a Buddha, you state that if there is a mistake to be made on the spiritual path, you’ve probably made it. Would you say there’s any particular “mistake” on your path that has offered an opportunity for the most growth and development?

I think since I got involved in this whole thing so young I’ve never been really clear how much was me growing up and just becoming a little bit more mature, and how much meditation prevented steering me in a direction that I might have taken otherwise. I was meditating before I started really drinking or having sex, or any of those sorts of things that we do. I feel like when I look back on the mistakes on my spiritual path, it’s more often just not being present with what’s actually going on as opposed to me spinning out of control and punching the Dalai Lama in the face. I don’t have those sorts of stories. But, I do feel like there are times when I definitely didn’t show up for my life, and as a result, I missed out on something good. I’m trying to get better about that. There are definitely ways that I’ve caused harm over time, and I know it. The path of making mistakes, as I say in the book, is very valuable, because you could, if you don’t live a life of awareness, make the same mistake thirty times. But, if you actually have some sense of “I don’t want to keep causing harm,” or “I don’t want to harm myself in this way,” then, ideally, you learn from it and don’t repeat that same mistake.

What are your plans after the tour ends?

Well, I founded a non-profit about a year ago called the Institute for Compassionate Leadership. We’re launching our first class in January. It’s a leadership training and job placement organization geared toward young-ish people – primarily twenty-one to twenty-eight-year-olds, although we accept everyone – who want to help the world and they’re not exactly sure how to do that or how to get work in that field. So, we put them through a process that includes meditation, community organizing, and traditional leadership skills, and get them focused on gun control or poverty reduction, or whatever it might be that they want to do. Then, we have this great network of recruiters who help them find that work. That’s like my main gig, and I would love to be able to devote more of myself to it once I’m off the tour, because things are definitely a little strained with me being in a different city every day. So, that’s the next six months. And then, The Buddha Walks into the Office comes out in September of next year.

Is that going to be an elaboration on chapter four, “Work Like a Buddha”?

Yeah. It is. It’s also an elaboration of the work I was just talking about. It’s about how we actually figure out who we want to be as opposed to what we want to do, and how we can actually go down a career path that’s helpful and being a benefit to the world. It’s about positioning ourselves in the work-world so we’re actually maximizing our time and helping society the most.

Readers can contact Lodro through his website (lodrorinzler.com) and connect with him on Twitter (@lodrorinzler).