Vampires have been present in both religious and cultural narratives across many different times and places. This continued presence has firmly established them as figures representing cultural anxiety and taboo – from xenophobia to fears about race and sexuality. The vampire’s origins are religious, with it beginning as something humans could turn into if they transgressed religious boundaries or fulfilled a number of superstitious criteria. ((See Wayne Bartlett and Flavia Idriceanu, Legends of Blood: The Vampire in History and Myth (Connecticut: Praeger Publishers, 2006).)) Once a demonic figure, however, the vampire has undergone various reincarnations in order to give each era the “vampire it needs.” The narrative use of the vampire has changed with cultural attitudes, and modern vampires seem to be the antithesis to their predecessors, seeking redemption and having strong religious convictions. This has particularly occurred in a post-9/11 world, and the figure’s presence in television series such as HBO’s True Blood (2008) offers viewers a creative way to engage religious, sociocultural, and political themes. More specifically, however, the vampires on the show allow viewers the opportunity to perhaps examine contemporary Muslim identity and misdirected cultural assumptions that have escalated since 9/11.

The understanding of the vampire as a different race – ridged forehead, hunched, animalistic, or differing in speech and gesture – has continued throughout the figure’s twentieth-century history. During this time, the vampire really grew into its fangs, becoming a horror-genre staple in literature and film. Since the turn of the century, however, there has been an even more noticeable change, which has allowed the vampire to take on aspects of social anxieties and engage cultural markers of identity. Although the vampire has always been popular, there was a saturation of vampire narratives in the media – on television, film, and literature simultaneously – that offered an apolitical way of discussing sensitive topics and issues that were often taboo, and doing so in a way that offered a commentary without outwardly making claims or assumptions. The humanization of the vampires, however, was the main difference with these types of narratives: they could now go out in daylight with minimal consequence and get their blood from other sources, such as blood bags, animals, or bottles, and avoid killing humans.

The vampire typically starts out as a human and is “turned” – thus embodying both the human and the monstrous in the same figure. Aesthetically, there is little difference between the human and vampire, causing us to question what it is exactly that makes them different. This, in part, explains why it has been almost inevitable that the vampire eventually be used in the way it has. With its appearance, assimilation with other humans is relatively easy, and given their life span, they have plenty of time to learn the gestures and behavior that will enable them to fit in. This has been the case in narratives since 2001, where the vampire is presented in familiar surroundings: in schools (Twilight and Vampire Diaries), hospitals (Being Human), and bars (True Blood). These narratives focus on the interaction between the humans and the vampires, and in particular, how well the vampires do at “passing” as human. This dichotomous nature of the figure is central to the themes of identity that run through modern vampire narratives. While they may aesthetically identify as “vampire” – fangs, pale skin, etc. – they are trying to behaviorally identify with the humans by following a code of morality and social norms set out by society.

Following the aftermath of the events of 9/11, topics such as religious faith and affiliation became tricky subjects to broach on screen, and representations of overt faith – mainly Islam – became less frequent and fraught with allusion to fundamentalists such as al-Qaeda, who perpetrated the attacks on the Twin Towers. The representation of Islam has been a difficult line to walk on screen, and the links between Islam and terrorism have been consistently reinforced through the media, making it difficult to tackle without being politically divisive. True Blood, however, based on Charlaine Harris’ The Southern Vampire Mysteries novels, expressed the conflicting attitudes that came with fundamentalism, and became an immensely popular series in doing so. The series offered an American take on the vampire, which, through its history, has become a patchwork of cultures and fears and has been modified accordingly. Moreover, the ability of vampirism to function as a symbolic ideological affiliation allowed for a more nuanced correlation between it and mainstream religious affiliations on the show.

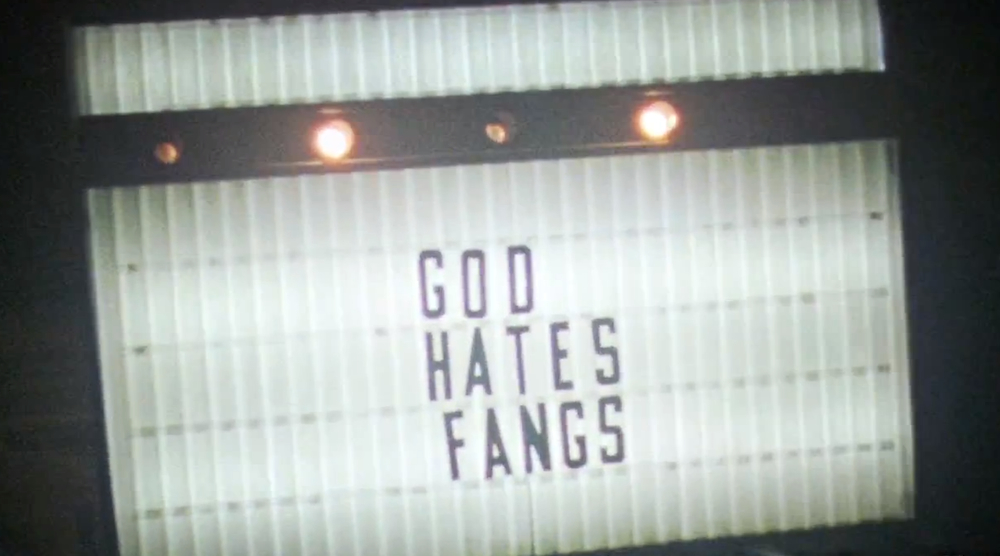

The series focuses on Sookie Stackhouse, a telepathic waitress who lives in the fictional town of Bon Temps. The world of True Blood is defined by the presence of vampires who have “come out of the coffin” and are positioned as a minority fighting for their rights in the United States. They encounter a strong negative response, with a somewhat religious bent: the title sequence features a billboard stating, “GOD HATES FANGS,” a clear allusion to the actions of groups like Westboro Baptist Church.

The Fellowship of the Sun, a Christian fundamentalist church in the series, leads the charge against the vampires, recruiting good clean American boys in their war against a perceived evil. The church is led by the Reverend Steve Newlin who courts the public via televised debates with the leaders of the American Vampire League, an organization promoting vampire rights, providing an opposing opinion to the acceptance of vampires. Newlin’s Light of Day Institute recruits young men and women and takes them on boot camp-style events, immersing them in the Fellowship’s ideology and beliefs. Throughout season two of the series, the Fellowship is revealed to be an extreme opponent to vampires, even planning horrific sacrificial rituals where vampires are burnt on the cross as they “meet the sun.” In the world of True Blood, vampires are an affront to the American identity, and God is the poster-boy for patriotism.

While themes engaging real-world issues related to sexual identity and gay rights are easily discernible, correlations between anti-patriotism and Islam are made explicit through a number of scenes in the series. For example, while role-playing in “Keep This Party Going” (S2:E2), Jason Stackhouse, Sookie’s brother and new recruit to the Fellowship, snaps an American flag in half to use as a stake against a “vampire” and is later chastised by fellow members of the group, who ask: “You some kinda Muslim buffy with a dick?” The implication that Islam runs counter to American values is obvious, and the response by the Fellowship offers an aggressive satire on the need for a response.

Suicide bombings, religious-based hatred, and the mentality of “us” versus “them” in the series have real-world implications, but can be interpreted in a variety of other ways, allowing the show to help viewers form their own opinions without unduly influencing popular opinion about Muslims or Islam itself. This is what George W. Bush’s administration had been aiming for after 9/11: an urging against “profiling,” whether racial or religious. The portrayal of humans versus vampires in True Blood is not as simple as good versus evil: there are examples of both on either side, stressing the idea that it is not the religion that defines good or evil, but people and their choices.

When Jason is taken in by the Fellowship, viewers are able to consider the reasons behind someone making a choice to become involved with a fundamentalist group. According to Jonathan Bassett, Jason’s involvement revolves around him feeling “special”: there is a “desire for symbolic, rather than literal, immortality that motivates Jason’s newfound religious zealotry, as he wants to feel that God has a purpose for his life, that he is special.” ((Jonathan Bassett, “Ambivalence about Immortality: Vampires Reveal and Assuage Existential Anxiety,” in Fanpires: Audience Consumption of the Modern Vampire, ed. Gareth Schott and Kirstine Moffat (Washington, DC: New Academia Publishing, 2011), 24.)) In a wider sense, this could be because the “human condition gives rise to a need for a sense of some kind of transcendent significance.” ((Ibid., 23.)) This transcendent significance is often “found” in religion, regardless of the extremity; Jason seeks this, but the role-playing example above displays his inability to move beyond the given patriotic identity assigned by the Fellowship. The focus on a metaphorical figure (the vampire) as a target for religious-based hatred – and one that embodies a threat to the American identity – also provides viewers with a depoliticized context for exploring the motivations behind real-world fundamentalist religious groups such as al-Qaeda and the Westboro Baptist Church. ((Regardless of who is specifically being represented here, the depiction allows for an understanding of extremist attitudes that are generally observed in the West.)) As Roland Barthes notes in his Mythologies: “In a context where we could not openly process the horror we were experiencing, the horror genre emerged as a rare protected space in which to critique the tone and content of public discourse. Because they take place in universes where the fundamental rules of our own reality no longer apply.” ((Roland Barthes, Mythologies, trans. Annette Lavers (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1972), 58.)) The alternate reality of True Blood allows American viewers to critique and explore attitudes towards a religious minority such as Muslims through the figure of the vampire, but in a setting that allows them to do so outside the sensitive realms of contemporary politics and religion.

Although the vampire has become increasingly humanized, it still contains an element of “otherness.” In True Blood, there is an increasing shift from classifying the vampire by “race” to a classification based on actions and belief. The vampires in True Blood who “mainstream” – that is, act more like humans – are accepted, whereas the ones who follow their nature and act against human societal guidelines are shunned. The same thing occurs for the humans, giving viewers unsympathetic characters and showing them to be hypocritical; the members of the Fellowship of the Sun are treated with contempt by many of the main characters (who are human and Christian) and the overall tone of the show towards them suggests a condemnation. Other characters display varying degrees of faith, and this helps the audience understand that faith does not necessarily pigeonhole someone, even if it is an aspect of their identity. Similarly, viewers are presented with a variety of vampire characters, but the overriding characterization is that of a sympathetic minority who is being persecuted based on their history or the actions of a few, much like the status of Muslims in the United States after 9/11.

But, why use fictional creatures to symbolically engage the Muslim identity – or any sort of marginalized identity in the United States for that matter (Christians in the series, after all, do not receive such an elaborate metaphorical treatment)? Although the creator of the series, Alan Ball, has not indicated that the vampire-Muslim relationship was his particular goal, he has indicated the desire to “play with the politics/religious angle, since that seems to be something that never stops.” Returning to Barthes, this particular sort of encoding might be necessary in order to avoid a politicization of an exploration or commentary on Islam or Muslim identity. Following 9/11, the backlash against the Muslim community was palpable. Portraying Muslim figures on screen became difficult. There were some attempts on television series such as The West Wing and 24, and later, Homeland, but these came under accusations of Islamophobia: a large proportion of the Muslim characters were only featured as terrorists. In these instances, Islam was pigeonholed as shorthand for “enemy,” perhaps due to the difficulties in understanding it and the associations with 9/11. Laila Al-Arian claimed in Salon that Homeland was “TV’s most Islamophobic show,” denouncing the character of Brody as “an awful pastiche of American fears and pseudo-psychology” and arguing that “it is demonstrated ad nauseam that anyone marked as ‘Muslim’ by race or creed can never been trusted.” Peter Beaumont asserted in The Guardian, “It does not matter whether they are rich, smart, discreetly enjoying a Western lifestyle or attractive: all are to be suspected.” This representation of Muslims returns to the idea of identity being defined by religion, but also confounds “otherness” (as a religious and cultural minority, or as part of a vampiric race) with “enemy.” In speeches following the attacks, President Bush urged against racial profiling, but this has occurred again and again, even in the fictional realm of television and film. ((For example, films such as Syriana (2005), Babel (2006), and The Kingdom (2007).))

True Blood, however, arguably takes the metaphorical tools and builds a more complex narrative that interrogates the fear and ignorance towards the Muslim “other.” The stereotyping against the vampires, mainly due to ignorance, damaged their view of the world and its social norms. This is arguably similar to the reactions some Muslims faced when al-Qaeda claimed responsibility for their attacks, and the series’ religious response to the “other” echoes Bush’s War on Terror crusade. Vampires and Islamic terrorists, in their rejection of Christianity, are also similarly deemed “un-American,” as patriotic identity also gets easily confounded with faith in this context.

Sociologists such as Jeffrey R. Seul have repeatedly explored “religion” as a marker of identity, which has become increasingly relevant since 9/11 – when religion became central to the definitions of “us” and “them,” ((See Jeffrey R. Seul, “Ours is the Way of God: Religion, Identity, and Intergroup Conflict,” Journal of Peace Research 36 (1999): 553-569.)) and when a particular religious identity became unfortunately linked with violence and intolerance in the United States through media proliferation. As Christopher Vecsey states, “the media tended to see the post-9/11 world divided into the west and Islam.” ((Christopher Vecsey, Following 9/11: Religion Coverage in the New York Times (New York: Syracuse University Press, 2011), 273.)) There was a need to differentiate between the identity of the attackers and the identity of the victims – the most obvious difference being the religion that al-Qaeda had acted in the name of. Salman Rushdie points out that “God is America’s answer to its crisis of identity,” ((Salman Rushdie, Imaginary Homelands: Essays and Criticism 1981-1991 (New York: Penguin Books, 1992), 391.)) and this is evident both in True Blood and the public and media response to 9/11. Examining the link between patriotism and faith, Deborah J. Schildkraut finds that “Christianity has played a central role in defining American identity.” ((Deborah J. Schildkraut, Americanism in the Twenty-First Century: Public Opinion in the Age of Immigration (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 44.)) Thus, patriotism, particularly as it is represented in True Blood, appears to be inseparable from faith, or is perhaps the crucial aspect of it. Both homegrown terrorists and vampires seem to threaten the very nature of the American identity, displaying a common heritage betrayed by difference.

In contrast, however, Jules Zanger asserts that the “new” vampire is “resolutely American,” portraying at once the “other” and the familiar; ((Jules Zanger, “Metaphor into Metonymy: The Vampire Next Door,” in Blood Read: The Vampire as Metaphor in Contemporary Culture, ed. Joan Gordon and Veronica Hollinger (Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1997), 19.)) this explains in part why the vampires in True Blood are simultaneously used as outsiders, and the victims of a reversed form of terrorism, thereby enabling Americans to sympathize with their experience despite their alien status. These vampires are representing the Muslim – not the Muslim terrorist – and a stereotypical view of Muslim identity that emerged due to racial profiling and fear about religious identities in the post-9/11 era. The positioning of the vampire as Muslim (which, due to the varied portrayals of the vampire on the show, can represent the wide array of identities and approaches to Islam) allows viewers to gain a different perspective on the persecution of a group due to their perceived identity.

True Blood takes the need for retaliation that followed 9/11 and highlights the dangers in this approach by casting the targets (in this case, vampires) as victims. While the vampires are, as a group, morally complex, the “war” waged on them by the Fellowship serves as a crusade against a stereotype rather than a reality, which interrogates the binary division between “us” and “them.” The similarities between the language Bush used when launching the War on Terror and that of Steve Newlin and the “recruits” of the Fellowship are undeniable. The most obvious correlation is when Newlin, aping a speech by Bush, asserts in “Timebomb” (S2:E8), “You’re either with us, or against us.” When the situation comes to a head, and there is a potential war, attempts to negotiate are met with Newlin’s retort: “I will not negotiate with sub-humans,” a clear reference to Bush’s assertion that “We do not negotiate with terrorists.” This, again, through a correlation between both vampire and Muslim, demonstrates the problematic nature of classification based on a religious identity alone, and the danger of “normalizing” minority and fringe views.

The vampire in True Blood allows for a level of detachment from the difficult identity politics following 9/11, and therefore a safer way of questioning responses to differences of faith, morality, and lifestyle. To posit the vampire as Muslim simply highlights the need for a way to examine attitudes towards them. By positioning the Muslim as a figure that has a complex moral history and has evolved to represent more than its stereotype, it begs us to question the stereotypes that have been proliferated throughout the media (much like the vampire). We are shown a side of a perceived “enemy” that is often not shown, and ultimately, exposes the complexities of identity and cultural assumptions.