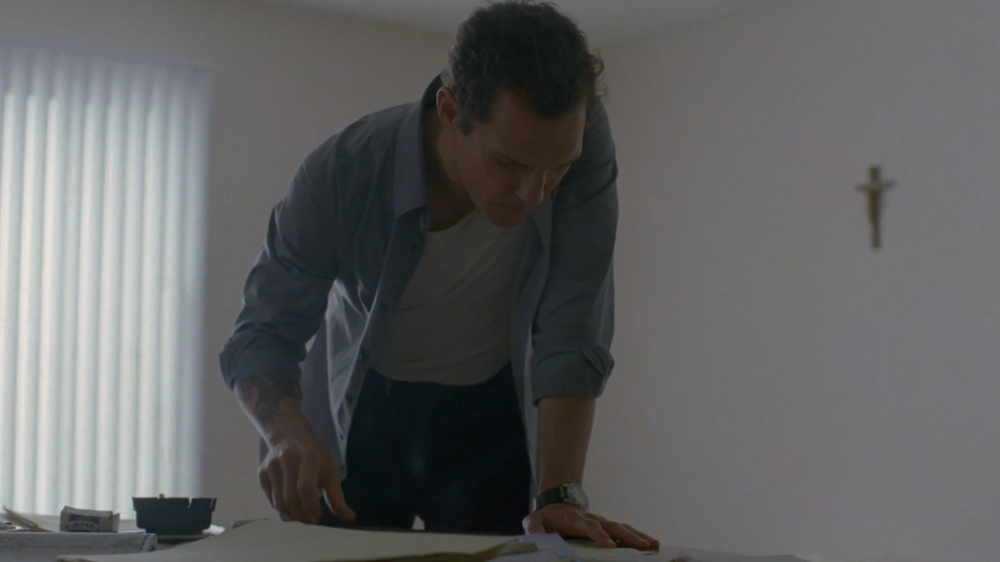

The first season of HBO’s noir anthology series True Detective begins with an intriguing discussion between Louisiana homicide detectives Rust Cohle and Marty Hart about an item hanging on the wall in Rust’s apartment: a crucifix. Most of the season takes place during 1995, following an elaborate and strange murder: a nude victim posed against a large tree, kneeling, with antlers secured to her head, surrounded by various, eerie objects made out of twigs and twine. After leaving the scene of the crime in the first episode (“The Long Bright Dark”), Marty recalls the crucifix he noticed earlier in Rust’s apartment, clearly uneasy about what they just saw, and likely seeking the comfort of one he assumes shares his beliefs: “You’re Christian, yeah?” “No,” Rust forcefully replies. “Well, what do you got that cross for in your apartment?” Marty confusingly responds. “It’s a form of meditation,” Rust states. “I contemplate the moment in the garden…the idea of allowing your own crucifixion.” ((Various passing remarks and instances throughout the season suggest that Marty is at least nominally Christian.)) For Rust, who is expressively not Christian, the image of cross and corpus appears to initially serve a much different purpose than what his partner assumes at first glance (that it represents Rust’s belief in a certain savior). But, a closer look at how Rust’s peculiar interpretation of the image aligns with his actions and voiced beliefs throughout the season demonstrates that the crucifix actually functions in a very similar way for him as it does for those reading the typical sort of Christian meaning into it, albeit without the latter’s theological constraints. Drawing on concepts and theory in semiotics, and specifically Roland Barthes’ semiological levels and notion of “myth,” Rust’s interpretation of the crucifix can be understood as equally indicating a sacrificial reading and ideological position that runs parallel to the perspective and worldview characterizing a more traditional Christian reading of the image.

Understanding how Rust’s perception of the crucifix fits into this scenario is an important aspect of this analysis, and the conceptual maps that underlie interpretative processes play a large role in how images of this sort are actually seen and appreciated. Cultural theorists use the term “code” to distinguish such conceptual maps used for interpreting images and finding meaning in them. According to Stuart Hall, codes are what stabilize and fix meaning, telling us “which concepts are being referred to when we hear or read which signs.” ((Stuart Hall, “The Work of Representation,” in Representation: Culture Representations and Signifying Practices, ed. Stuart Hall (Milton Keynes: The Open University, 1997), 21.)) Such meaning has much to do with social and cultural conventions relative to time, place, and those who are actually doing the hearing or reading. One of the implications of this relativity is that meaning “can never be finally fixed”; since social, cultural, and linguistic conventions largely determine what is “meaningful,” meaning cannot be considered inherent. It is necessarily constructed. ((Ibid., 23.)) As Hall states, “The main point is that meaning does not inhere in things, in the world. It is constructed, produced. It is the result of a signifying practice – a practice that produces meaning, that makes things mean.” ((Ibid., 24.)) Since meaning is not simply given, an interpretative act must occur in order for it to be taken. But, certain conventions do change over time, so meanings also inevitably change, which is why meaning is never fixed once and for all. The crucifix, then, only becomes meaningful and useful to Rust through a process of decoding; the same occurs for Marty as well, no matter how taken-for-granted his decoding – as a “Christian” reading – may appear in this context.

It’s clear that Rust is aware of the typical reading of the crucifix; his understanding of the “moment in the garden” leaves little doubt about this fact. Though instead of adopting what Colleen McDannell calls the “intentions of a clerical elite” or the “idiosyncratic whims of the masses,” ((Colleen McDannell, Material Christianity: Religion and Popular Culture in America (Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1995), 17.)) Rust colors the image with his own meaning and ideological flavor. Aware of the more mainstream representational role of the crucifix, Rust chooses to push back against it in order to adapt it for his own purposes. McDannell notes that religious objects can and are used in many different ways, not necessarily reflecting those clerical intentions or mainstream perspectives. ((Ibid.)) Rather, using their own cultural “tools,” people construct meaning in their own way, fashioning unique responses to “their own spiritual, psychological, and social longings.” ((Ibid.)) Roland Barthes notes that “signs” are also “drawn from a cultural code” and that the readings of the same image necessarily vary on an individual basis, depending on “the different kinds of knowledge – practical, national, cultural, aesthetic – invested in the image” by those reading it. ((Roland Barthes, “Rhetoric of the Image,” in Image-Music-Text, trans. Stephen Heath (New York: Hill and Wang, 1977), 46.)) Rust’s crucifix benefits from a semiotic analysis in this regard, when framed as a unique sign carrying a certain connotative meaning relative to those doing the interpreting.

Generally speaking, classical semiotics rests on the appreciation and breakdown of the “sign”: a word or image’s form (the “signifier”) and the concept triggered by the form (the “signified”). ((Hall, 31.)) The relation between signifier and signified is also largely determined by cultural frameworks for interpretation, i.e., the “codes” noted above. Just like various conventions, these change, and “every shift alters the conceptual map of the culture, leading different cultures, at different historical moments, to classify and think about the world differently.” ((Ibid., 32.)) Barthes recognizes the basic distinctions between signifier, signified, and sign, but discerns another operative semiological level: myth. ((Roland Barthes, Mythologies, trans. Annette Lavers (New York: Hill and Wang, 1972), 114.)) In this “second-order semiological system,” Barthes states, the sign of the first system becomes the signifier for the second, pointing towards a broader, ideological concept. The resultant sign at this level is referred to as “signification”; for Barthes, this “signification” both imposes a certain sort of connotative meaning onto viewers and reflects an underlying ideological system (i.e., a “mythology”). ((Ibid., 117.))

In Mythologies, after analyzing a number of “modern myths,” Barthes famously uses a Paris Match magazine cover image and the myth of “French imperiality” to illustrate his main points; his model, however, can easily be applied to the crucifix in Rust’s apartment. ((For Barthes’ analysis of the Paris Match image, see “Myth Today” at the end of Mythologies.)) The most recognizable signifiers of the image are the cross – made of two intersecting pieces of wood – and the male body on it. These details likely signify the obvious for most viewers (and, without question, Marty): a crucifixion. Cultural coding (that of a modern, Western audience, generally familiar with Christian values and associated narrative themes) encourages viewers (and Marty) to read this image as signifying not just any crucifixion, but the crucifixion of Jesus. Thus, the “sign” at this level is Jesus’ crucifixion, which aligns with Barthes’ first-level semiological system. For Marty, and most other Christians, Jesus’ crucifixion signifies his self-sacrifice for the sake of humanity. The resultant signification of the image at this mythological level becomes the suffering of their divine savior accompanying his atonement for them, with the image serving as a representation of faith in this deity and a reminder of this sacrifice. But, as outlined below, the image signifies something a bit more general for Rust and imposes a slightly different sort of meaning: a willing self-sacrificial act, with a connoted signification that points towards self-sacrifice for a greater purpose. This is where the two readings both converge and diverge: variation in signification. Both can be broken down to be broadly conveying the idea of a willing self-sacrifice for a greater purpose, varying only in – and because of – the frameworks involved in their interpretations.

Marty’s bafflement over Rust’s use of the crucifix frames the latter’s interpretation of the image in an alternative sort of way for viewers: Rust is not a Christian, so the importance he places on the crucifix is surprising. Marty’s reading of the image, determined by his own conceptual map, sees that self-sacrifice as divine atonement for sin and the saving of humanity from the prospect of eternal suffering. It is, in other words, explicitly theological. But, Rust’s reading forms a “secular” version of this sacrificial myth, without the incorporation of a deity: it simply embodies the generality of a self-sacrificial and saving act. This reading clearly aligns with his motives throughout the rest of the season, placing his actions in congruence with this mythic variation.

Seven years after Rust and Marty supposedly closed the 1995 homicide case, Rust comes across new evidence suggesting they didn’t actually find the killer and that he had been continuing his gruesome habit throughout the area without drawing the detectives’ attention. Rust becomes convinced that some sort of cover up took place back in 1995 – and continued to take place thereafter – especially when he starts to probe a little deeper into the connections the murders might have to community leaders and public officials. The odd backlash he receives from his superiors – and, unfortunately, Marty – eventually pushes him to quit the department and leave the state. But, the responsibility he feels for the lives lost at the killer’s hand since 1995 haunts him, forcing his return to Louisiana in 2010 to personally work on the case for the next two years in order to resolve the debt he feels towards the community he mistakenly left to the killer’s murdering whims. Rust’s actions, then, are directed toward saving the community from the pain and suffering – at the expense of his own, viewers discover – of this maddened murderer.

Throughout the season, Rust noticeably dwells on the dilemma of his own existence. Having suffered through the personal tragedy of the loss of his young daughter, a resultant failed marriage, and a number of years undercover spent with various criminals, violent activities, and hard drugs, it is no wonder that he has such a diminished view of the world (“a giant gutter in outer space”), which he doesn’t shy away from expressing to Marty during their discussion in the first episode, and of humanity: “creatures that should not exist…things that labor under the illusion of having a self.” He takes this derision of humanity even further: “A secretion of sensory experience and feeling, programmed with total assurance that we are each some body, when, in fact, everybody’s nobody. I think the honorable thing for our species to do is deny our programming. Stop reproducing. Walk hand-in-hand into extinction. One last midnight. Brothers and sisters opting out of a raw deal.” But, Rust doesn’t necessarily want to die – at least not by his own hand. When Marty asks him during that same conversation what the point is of even getting out of bed in morning, Rust simply replies, “I tell myself I bare witness, but the real answer is that it’s obviously my programming, and I lack the constitution for suicide.” If the crucifix in his apartment is understood as an object of meditation on the idea of allowing one’s own crucifixion, i.e., allowing one’s own sacrifice for a greater good, then Rust’s perspective and actions by the end of the season might make a bit more sense, based on the ideology the image connotes.

Though Rust confesses that he does, indeed, lack the constitution for suicide – that he is not interested in taking his own life – he does not exactly indicate how he feels about the prospect of giving his life in that diatribe quoted above. In fact, as can be discerned from later scenes, his contemplation of the image relates directly to underlying sentiments he has for saving those in proximity to the killer, even if he is not explicit about this connection, and even if he appears to not care much for what happens to “creatures that should not exist.” Although a sacrifice of this sort might simply be serving as Rust’s reason to die – something to allow him to escape this “ghetto” – his later actions make it difficult to shake the deeper implications of his fixation on an image he identifies as importantly signifying a willing self-sacrifice for a greater purpose.

When a new murder surfaces in 2012 (present day) that strongly resembles the one from 1995, Rust contacts Marty (now working as a private investigator, having retired from the police department in 2006), hoping he’ll assist him in finally closing the case. During the penultimate episode of the season (“After You’ve Gone”), Rust and Marty, having not seen each other for the past ten years following a heated argument and Rust’s departure, catch up over a couple beers. Marty eventually asks Rust why he came back to Louisiana. “A man remembers his debts,” Rust replies. “We left something undone. We gotta fix it.” As Rust implores Marty for his help in pursuing the case they supposedly closed in 1995, Marty’s frustration grows as he asks why he should bother helping him. “Because you have a debt,” Rust replies. “Because the way shit went down in ’95. This is on you too, buddy.” After showing an initially unconvinced Marty the representational evidence he has collected of this “debt” – a storage unit filled with his work for the past two years, including corroborating evidence that some sort of cover-up did take place – Marty agrees to help him and is equally convinced they left the job unfinished, that the killer has still been committing murders, and that Rust was correct to revisit the evidence back in 2002. Interestingly, recognition of that “debt” appears to involve Marty in Rust’s reading of the crucifix. Though his interest in assisting Rust is likely based on his self-identification as a public servant, it’s also important to remember that a willing self-sacrificial dimension characterizes both of their readings of the image.

As the season concludes, the connection between Rust’s actions and the way he views the crucifix in his apartment becomes clear. When Rust and Marty finally discover and kill the man responsible for all of the murders, both of them are severely injured, though Rust is in much worse shape. At first, it isn’t clear that Rust is even going to survive his stay at the hospital. And when he does eventually come out of his post-surgery coma near the end of the last episode (“Form and Void”), his remarks to Marty make it sound pretty obvious that he didn’t think he should still be alive – that he might have been anticipating that the whole time as well: “I’m not supposed to be here.” Perhaps, Rust felt his life was fated in some way – that his suffering would be for the sake of others in some sort of sacrificial act – since it first became, presumably following the death of his daughter, a “circle of violence and degradation” (“After You’ve Gone”). Indeed, as Rust follows the killer earlier in the episode through a gruesome and twisted maze of debris and remnants of previous victims in the woods, he heeds the murderer’s call: “Come die with me.”

Later, when Marty takes Rust outside of the hospital to get some fresh air, he says it again: “I shouldn’t even fucking be here, Marty.” Rust then proceeds to tell Marty that while he was unconscious, he felt like he had been reduced to a “vague awareness in the dark.” Feeling “his definitions” fading away, he felt something deeper – something towards which his vague awareness was moving. He could feel the warmth and overwhelming love for and of his daughter and father, waiting for him so they could all fade away together. In between sobs, he tells Marty that, instead of joining them in death, he woke up. To comfort his partner and take his mind off of what had happened, Marty reminds Rust of how he used to look at the stars and make up stories about them in his youth in the Alaskan wilderness. Rust tells him there is just one story – the oldest: light versus dark.

The deeper connections the killer had to public officials that Marty and Rust exposed are disparaged and disregarded while the two are hospitalized, leaving the guilty to continue their reign of corruption and violence. Though Rust didn’t die in resolution of his “debt,” the fact that they didn’t get everyone involved leaves viewers with the allusion that he might not stop trying – that he will continue to try and truly finish the job. His resurrection of sorts, then, gives Rust the opportunity to continue to fight that battle of light versus dark with an elated sort of optimism: looking up at the stars, Marty tells Rust that it looks like the dark has a lot more territory. Rust says he’s looking at it wrong: “Once there was only dark…if you ask me, the light’s winning.”

By the end of season, it becomes clear that Rust’s initial remarks regarding his use of the crucifix correlate to an underlying ideological position it informs, clarifying his sacrificial suffering and for what he feels his life should be given. His reading of the crucifix also highlights the varying ways in which viewers interpret images and how those interpretations both arise and reflect broader ideological positions. From a semiotic – and Barthesian, in particular – perspective, the crucifix hanging on Rust’s wall can be understood as representative of a parallel sacrificial reading of this traditional Christian image: a willing self-sacrifice for a greater purpose. The difference between the two readings rests on the manner in which the image is decoded, determined by relative conventions and perspectives: salvation from an otherwise eternal suffering on the one hand, and salvation of a community from a gruesome killer on the other. Both demonstrate a willing self-sacrificial myth, differentiated only by their relative decoding and interpretative processes. Thus, the crucifix in Rust’s apartment serves as a larger representational model for how such interpretative processes take place and how they indicate broader sociocultural standpoints and personal beliefs.

This was an incredible read, thank you for your insight.