In a previous post, I discussed the character of the Cyclops in an ancient myth, Homer’s Odyssey, and a modern comic, Isabel Greenberg’s The Encyclopedia of Early Earth. In that post, I began from the well-known insight that particular stories are reworked in different times and cultures to remain relevant, and argued that the reworking of the Cyclops myth from Homeric epic to modern graphic novel reflected changing cultural understandings of selfhood between ancient Greece and the modern West. I also suggested an additional reason to explain the difference between Homer’s and Greenberg’s Cyclops, which I’d like to address in a bit more detail here: the medium of the graphic novel, which differs in a number of important ways from the literary/oral text of Homer’s Odyssey.

The difference between Homeric epic and the modern graphic novel begins with the well-known tension between “text and image.” The difference between these two mediums results in certain things being better suited to text, such as linear narrative, complex conversation, and complex psychology. Other things, meanwhile, are better suited to image, such as the depiction of monsters or broad allegories that can be understood in detail all at once.

The nature of the graphic novel as medium constricts the type of individualistic selfhood that I’ve identified previously, while enabling others. This mix of enablement and constraint suggests that the graphic novel, while seeming to be a distinctly modern medium, in fact is paired in complex ways, often in tension, with an individualistic identity paradigmatic of the modern West.

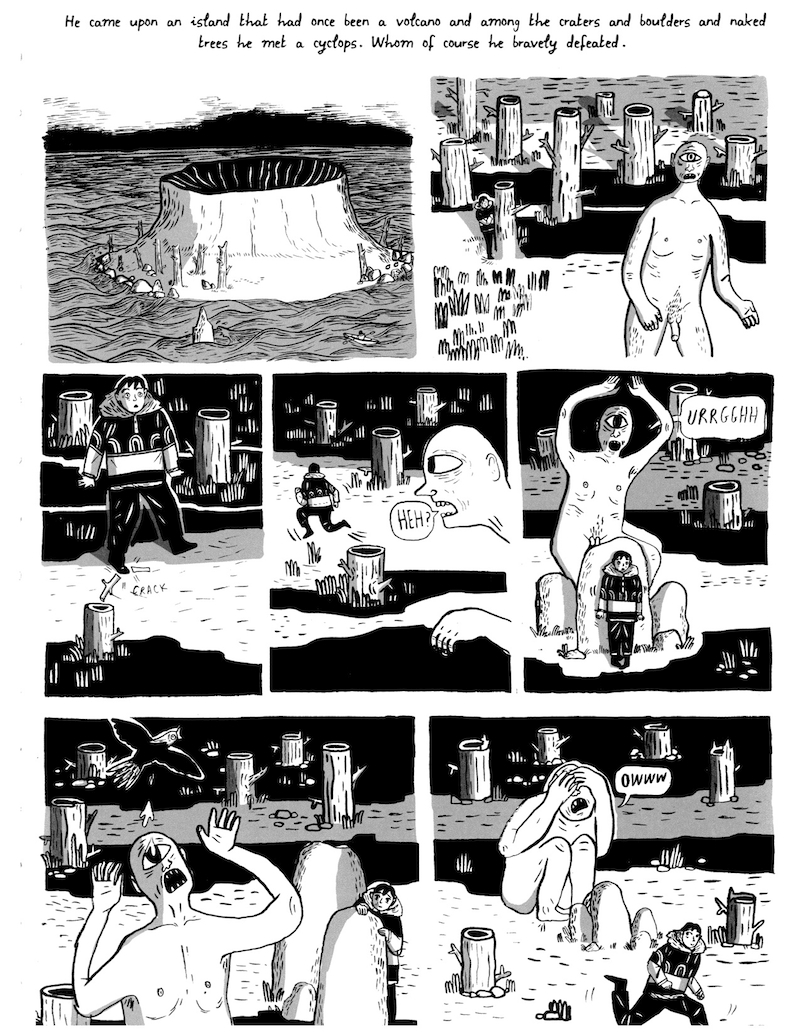

Greenberg’s Cyclops

This visual depiction of the Cyclops and the protagonist’s interaction with him lacks certain structural limitations as compared with an oral/literary text. For instance, the sequence of events lacks linear temporality through the presentation of images side by side. A reader can literally take in the entire sequence with a single glance, instead of being forced to read through a text line by line.

While Homer can narrate Odysseus’ progress into the Cyclops’ cave, the return of the Cyclops, and their interaction second by second, the temporal nature of the interaction in Greenberg isn’t clear. For example, the amount of time the hero traverses the island before running into the Cyclops is unclear, as is the period of time following his discovery/hiding and eventual escape. The entire episode can, in a sense, be temporally reduced to a single interaction separate from any distinct temporal markers.

For Odysseus, by contrast, the passage of time in this interaction was hugely important. Not only did he and his companions settle into the cave for some time to eat and rest – classic elements of hospitality – but Homer takes care to mention the return of the Cyclops at the end of the day, and the chores the Cyclops performs vis-à-vis his animals in the morning and at night. The actions of the Cyclops are pastoral, determined by the lot he was born into and the environment he inhabits. For Odysseus, this same environment conditions his social interaction with the Cyclops – what he needs, his requests as a guest, and so forth.

The lack of distinct temporality in the graphic novel account closely aligns with the modern, individualistic view of selfhood. Individualistic identity – as compared to ancient, socially-structured identity – is generally distinct from any particular time, or indeed any particular place. Instead, one’s identity tends to arise from particular beliefs, desires, and intentions that exist regardless of where one lives or how long one has been engaged in any particular job or pastime. Of course, it is important in some sense where you were born, for example, but if you spend your life on activities and passions that can and do occur regardless of your place of birth, then your selfhood can be defined as “individualistic” (modern) as opposed to “socially structured” (ancient).

By contrast, a pastoral life typical of the ancient world, whose elements of work are determined by the rising and setting of the sun in a particular place, stand in notable distinction to the knowledge economy, where one can work from any place and at any time. Regardless of where one is born today, goes the line of thinking, one can rise above one’s circumstances and in a sense move beyond any structural limitations, such as a lower-class family or socially-denigrated form of worship.

Indeed, this movement above and beyond the structural and temporal limitations of something like a pastoral life is a hallmark of modern selfhood. It is something of a marker of pride for Millennials that one can pursue particular interests or professional tasks from any place of one’s choosing. Modern selfhood, in other words, in both work and play, is more divorced from specific temporal markers as compared to ancient selfhood, and this type of selfhood is uniquely suited to depiction in the graphic novel with its own erasure of time due to its visual medium.

In other ways, however, this visual medium does not match up with modern, individualistic selfhood. As I mentioned above, the graphic novel does not particularly excel at depicting complex psychology. The visual medium struggles to get inside the head, as it were, of individual characters, being forced to do so via thought bubbles and generally simpler narration as compared to an expansive literary epic. The literary/oral medium can simply inform us of a given character’s psychological status and inner divisions on a particular issue, and can do so at great length and detail.

We see this very tension in the episode with the Cyclops. In Homer’s account, the decision to go onto the island, to enter the cave, to partake of the goods therein, and how to respond to Polyphemus’ aggression were all decisions subject to discussion and weighing of options by Odysseus. Indeed, Odysseus’ infamous “wily” nature speaks directly to the internal machinations of an active, astute, and strategizing mind.

This depiction of complex, inner psychology that defines “wily Odysseus” finds a close parallel in modern, individualistic selfhood. People today see their identity defined less by a particular job, family, or institution than by all the internal psychological elements, such as beliefs, desires, and intentions. While one can easily depict an occupation, a clan, a homeland, or an institution visually, the graphic novel struggles to depict complex, inner, and often hidden emotional and psychological states.

Note, for example, the depiction of our protagonist in Greenberg’s account: whereas Homer’s Odysseus is a notoriously complex character with visually hidden machinations (hence the “wiliness”), Greenberg’s hero is tough to psychologically read in his interaction with the Cyclops. Fear is readily apparent, but little beyond fear and perhaps surprise can be revealed through the image of his face. And while the adage “a picture is worth a thousand words” is surely true, the demands of a graphic novel are such that extreme attention to the nuance of every face in every panel is simply impossible. A serial with hundreds of panels, by its very nature, must lose some of the psychological complexity we see in a single, exquisitely rendered image.

So, the graphic novel, it seems, is closely attuned to modern individualistic selfhood in some ways, such as the erasure of clear temporal boundaries, while it struggles in other ways, such as the depiction of complex psychology. While we might think of the graphic novel as a uniquely modern phenomenon, it seems that it is a medium imperfectly suited to the type of selfhood widely present in the West.

This is not the end of the story, however. First, other areas of potential alignment (e.g., depicting monsters or allegories) or potential departure (e.g., complex conversation) have yet to be discussed and reflect the intersection of a complex medium with a highly nuanced idea of selfhood. And second, the graphic novel is by no means a monolithic medium: examples exist of illustrated novels that blend the line between novel and comic, and of comics that contain exquisitely rendered images along with complex psychology and dialogue. The story, in other words, continues to evolve, with the graphic novel and the modern world continuing to intersect and influence one another in a dynamic, ongoing way. This intersection will undoubtedly only deepen, with the graphic novel becoming increasingly complex, sophisticated, and a mainstream part of the Western literary and cultural landscape.