Released on December 3, 2013, and landing on Time’s list of the Top 10 Fiction Books of 2013, Isabel Greenberg’s The Encyclopedia of Early Earth re-tells many ancient Western myths in the context of its wider romantic narrative about a boy’s quest to find his true love. The mythological stories range from biblical subjects, such as the Tower of Babel, to ancient Greek epics like Homer’s The Odyssey. These tales are at once familiar and unfamiliar, as they draw from famous stories in the distant past but re-tell these stories in ways that sometimes radically depart from the originals.

This familiar-but-unfamiliar use of ancient mythology frequently appears in modern graphic novels. Especially with the huge influx of graphic novels in the last decade or so, the relationship between modern storyteller and ancient story has become increasingly visible, and increasingly complex. But, what exactly does this relationship look like? How are modern graphic novels appropriating stories from ancient mythology, and why? More specifically, which ancient myths do graphic novels pick, which parts of those original myths survive, and which parts are modified?

This column, starting with an episode from Greenberg’s Encyclopedia, will suggest answers to these types of questions. By analyzing a variety of modern graphic novels, ranging from Batman to Neil Gaiman’s Sandman stories, I will examine why certain elements of ancient mythology are retained in modern varieties while other elements are discarded or modified in certain ways.

Two factors are particularly central to my analysis:

First, the medium of the graphic novel itself. This factor includes the basic tension of “image versus text,” but also includes how the modern graphic novel in particular resists classical literary conventions, such as a linear narrative and a heroic protagonist. This picture-based medium excels at depicting certain things familiar to us from mythology, such as monsters or broad allegories, by presenting grand and detailed images. Yet, this medium struggles at accurately depicting other things that might appear in ancient myths, such as varying psychological states and complex conversation that are better relayed as prose.

Second, the modern graphic novel arises from, and in turn influences, our modern, Western culture. This culture is globalized, includes values, such as individualism, and contains an audience well versed in postmodern ideas and literature that lend a certain type of irreverent, cheeky, and highly culturally indexed humor. Thus, certain aspects of a given story that are important within the Hebrew Bible, for example, are omitted or given a humorous re-branding explicable to its modern audience. Other elements that may seem non-essential to the original myth, meanwhile, may be kept if they fit certain modern, Western sensibilities. In these ways, the modern graphic novel retains only certain elements of ancient mythology; thus, it maintains the relevance of these stories for a modern audience.

To illustrate some of these differences, let’s consider how the Cyclops episode in Greenberg’s Encyclopedia contrasts its apparent source in Homer’s famous epic:

In Homer’s original version, Odysseus and his crew land on an island as part of their wandering return home and venture inland to a large cave. The arrival of the Cyclops Polyphemus to the cave traps Odysseus and his crew inside, and Polyphemus wastes no time in casting aside the classic Greek notion of hospitality by eating several sailors. Eventually, Odysseus convinces the Cyclops to drink himself into a stupor, at which point the doomed Greeks blind Polyphemus by driving a stake into his eye. Odysseus and his remaining crew then escape the now-blind Polyphemus’ cave by riding along the undersides of the sheep, mocking him as they sail away.

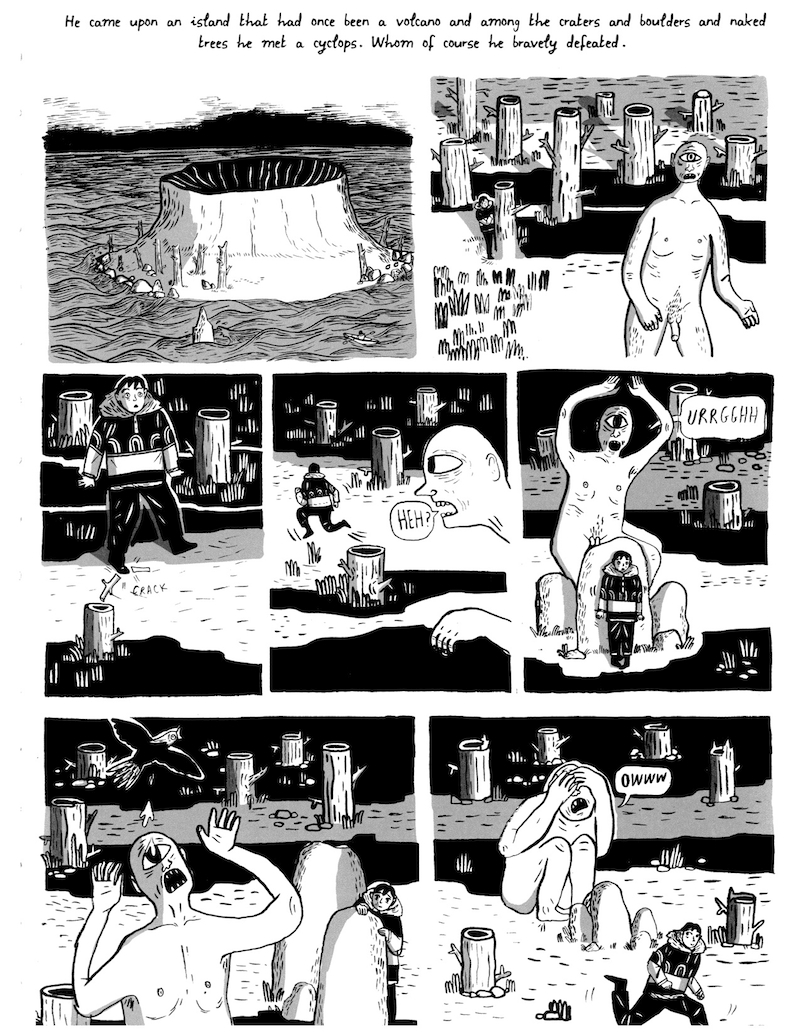

The Cyclops tale in Greenberg’s Encyclopedia reproduced here is much shorter, with notable differences that appear to reflect a modern – and noticeably individualistic – sensibility: the lack of other sailors accompanying Greenberg’s hero, and the humorously truncated escape as compared to Homer’s more lengthy, violent, and sober original.

In Homer’s tale, Odysseus’ identity is partly constructed around his role as the king of Ithaca, who is responsible for his fellow sailors. Homer uses Polyphemus’ eating of the sailors as a meditation on what it meant to be a member of Greek society – specifically, the role of hospitality and the civility that accompanied it. Greenberg’s episode, by contrast, involves no such construction of identity based on social obligation, focusing instead on the luck of the individual protagonist. The way that Greenberg understands her protagonist, in other words, is highly individualistic. This differs hugely from the way that the ancient Greek poet Homer understood Odysseus, and the Greek people more broadly – an understanding that was built upon identity as explicitly structured by society. This cultural difference in understanding and constructing identity between ancient Greece and the modern West suggests how and why Greenberg’s graphic novel changes Homer’s original epic tale.

Political commentators today fret about Millennials’ increased individualism, which encompasses personal, internal attributes, such as preferences, feelings, thoughts, and beliefs. Thinking of oneself as a unique collection of desires, emotions, and plans is an example of an individualistic identity. This can be usefully contrasted with a more socially constructed identity, where one understands oneself in terms of one’s family, lineage, wider clan, geographic location, or the religion of one’s ancestors. Of course, individual preferences, feelings, thoughts, and beliefs are often highly influenced by one’s wider social relations. But, where one locates identity – what one likes and chooses versus where one was born and to which family – points to the difference between individualistic identity and one that is socially constructed.

Like Homer, Greenberg does reflect on humanity and its place in a hostile, unpredictable world, though not in any socially constructed scenario, such as Odysseus’ struggles alongside his crew and the concept of obligatory social hospitality. Rather, Greenberg’s meditations occur when the protagonist is faced with situations of loneliness, confusion, or thwarted love. But, all of these situations can take place regardless of time and place; thus, they are easily relatable to a modern, Western audience with an identity typically based on personal emotions and preferences instead of on something like ethnicity and the town in which their fathers were born.

For Homer’s Odysseus, in other words, the episode with the Cyclops functions as a reflection on his identity as a civilized Greek from Ithaca, the land of his forefathers. For Greenberg’s hero, the episode with the Cyclops functions as a single obstacle toward the distinctly individualistic goal of true love (as opposed to Odysseus’ various affairs and lack of romantic language about his wife Penelope).

This difference raises a number of questions for us as readers Greenberg’s work, and of contemporary graphic novels in general: Does Greenberg’s individualistic hero, for instance, indicate a change in how we view the hero of Homer’s story? Do we now think of Odysseus less as a reflection of Greek culture, and more in the individualistic terms of our modern society? And does the graphic novel’s retelling of this ancient story change our perceptions and memory of it?

I think it does, as stories that remain relevant tend to inevitably change with the times, reflecting differing cultural attitudes and sentiments. But, an aspect we have yet to fully consider in this example is how the graphic novel itself, with its emphasis on images as opposed to poetry and lengthy prose, might reflect this particular cultural change toward individualism. Are poetic complexities and deeper psychological elements necessarily comprised, resulting in a mere superficial rehashing of meaningful stories? Or, do these adapted narratives find their rightful place within a new time and setting, and among a new sort of audience?

I invite you to start considering these types of questions as this column moves forward, and whether or not you feel contemporary retellings like Greenberg’s color our views and appreciation of ancient epics like The Odyssey.

What a great article! This is an incredibly insightful and thought-provoking analysis. I will be looking for more from this author in the days, weeks, and months to come!