One of the difficulties in talking about reading and religion is the question of what, exactly, is “religious reading.” In “Starting from Scripture,” I rejected the idea that religious reading involves only sacred texts or happens only within religious institutions. But, once we leave behind those relatively clear boundaries, how do we distinguish religious reading from any other kind?

I was thinking about this as I recently read through the latest choice in nighttime reading at my house: B.J. Novak’s The Book with No Pictures. It’s a children’s book, beloved by my four-year-old, and it is, as advertised, a text-only book. “You might think a book without pictures would be boring and serious,” it warns. The appeal comes when the words start changing from plain English into nonsense words and silly sounds…and the person reading it out loud has to read them anyway:

Here is how books work.

Everything the words say,

the person reading the book has to say.

That’s the deal.

That’s the rule.

No matter what.

Even if the words say…

BLORK!

The result is a lot of silly sounds and goofy words, and a child audience giggling at an adult reader compelled to yell “BA-DOONGY-FACE!” It’s a crowd-pleaser.

Naturally, as someone who studies reading, I always focus on that sentence about “how books work.” What exactly is going on when the book isn’t just a story, but a meta-story, about the act of reading itself?

In theater, this is called “breaking the fourth wall.” The term refers to sets where the “fourth wall” is the invisible barrier between audience and actors. Three walls of the room are visible, and the fourth is open to the audience. A fourth-wall break is a moment where the characters become aware of the audience, perhaps even respond to them or flee from them, or a moment that suggests that the characters inside the story know they’re in a story. In comedies like Ferris Bueller’s Day Off or Mel Brooks movies, this makes for funny asides and commentary on the plot; in darker examples such as The Ring or Funny Games, the audience is directly threatened or made complicit in the villain’s actions. By looking at the ways that texts lean on and break the fourth wall, we can identify something important about the relationship between author and reader, and maybe identify what makes some reading “religious.”

Children’s books often have fun with the fourth wall, like Novak’s book, or like The Monster at the End of this Book, in which Grover the Muppet begs the reader not to turn the page. But, playing with the fourth wall can be more subtle. Books that talk about books, or books that talk about the power of reading or the power of writing, are being somewhat self-referential. Examples include The Book Thief, which not only talks about the power of books but features a narrator who directly addresses the reader, or The Neverending Story, which offers not only praise but caution about the power of fantasy/the land of Fantasia. An aside about how books can change society subtly reminds the reader that he or she, too, is reading.

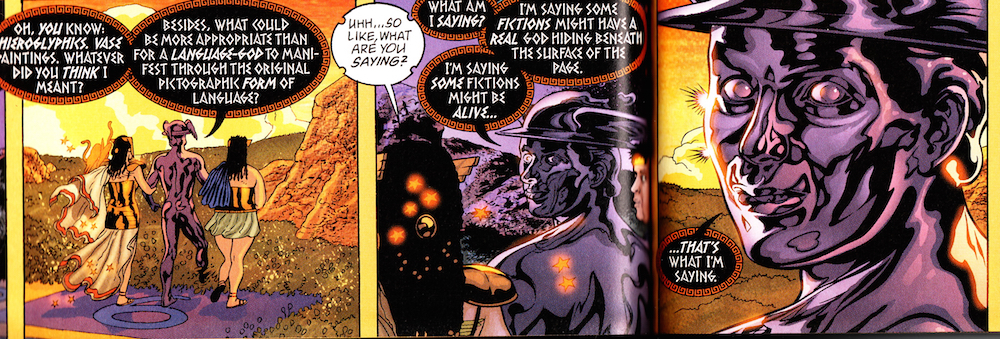

The most dramatic form of fourth-wall break comes from a direct address to the reader. When a character seems to see the readers on the other side of the page, or to speak directly to them, it can be startling. The opening of House of Leaves is such a break, where the epigram, “This is not for you,” discourages the reader from the first page. Graphic novels can play with this direct address through their visual aspect: Hermes’ reader-focused gaze in Promethea remains one of the most effective fourth-wall breaks for me:

Most scriptural narratives don’t break the fourth wall. In Genesis, there is no sense that Hagar realizes she is a character in a holy story, nor does Noah address the reader. The dialogues of poetry in the Song of Songs take place within the fourth wall, and the “set” isn’t disrupted by an address to the reader.

Sometimes a sacred text talks about itself, directly pushing on the fourth wall while not entirely breaking it (much like a soliloquy in theater). The Ramayana opens with an account of the composition and recitation of the Ramayana. The Qur’an frequently refers to itself as a Book and a clear guide to listeners (Surah 27:1, 38:29, and 2:185, among others). Even Jesus speaking about parables (Matthew 13:13) can be a kind of fourth-wall pressure.

Sacred texts have the strongest fourth-wall break when, like House of Leaves, they directly address a specific reader or listener. But, this can be defused if the intended audience is clearly not the current reader; e.g., if the audience is the Thessalonians or Philippians addressed in Paul’s biblical letters or the people of Nineveh hearing Jonah’s challenge.

What makes the fourth-wall break possible, though, isn’t just its presence in a book. A Christian is instructed to read the Sermon on the Mount not as a historic record of a speech, but as guidelines for instruction. Jews are instructed to see themselves as participating in the Exodus during Pesach and as standing at Sinai during Shavuot. It’s this connection between the general address of the text and the specific life of the reader that distinguishes, for example, “reading the Bible as literature” from “reading the Bible religiously.”

Trying to define religious reading in terms of the text is nearly impossible. The variety of genres in the Hebrew Bible alone means that a definition has to include poetry, law, psalm, history, creation myth, and prophecy. Requiring that religious reading include a reference to God kicks out some books and includes others; requiring that it be part of a canon or that it be read literally ignores other religious texts.

Trying to define religious reading in terms of what the reader does is a little more plausible; Paul Griffiths’ Religious Reading attempts this by defining religious reading as having a reverent, obsessional quality that carefully savors a text and submits to its authority. Even this version leaves out a lot of the pragmatic, everyday reading of non-virtuoso religious persons.

Is religious reading “religious” because of the beautiful obsession of Griffiths, the assertion of authority, the claims of literalism, or the trust that this is the best version of reality? Or does reading become religious when the reader accepts the mantle of “intended audience”? Maybe accepting the fourth-wall break means becoming the person for whom this story (or this book, this commandment, this savior) is meant!

This tentative definition of religious reading wouldn’t depend on a set of officially approved ways to read, which could pit literalism against metaphorical interpretation, or on a requirement for a creation story or an active divinity within a text, but on the relationship between reader and text. It marks the difference between a meaningful text, which can have life-changing effects but is addressed to every reader, and a text read religiously, where the meaning is directed to me.

I’m not yet sure how broadly applicable this definition of religious reading might be, nor am I entirely certain how I’d try and measure it among readers. But, I’m intrigued by the potential it has, and I look forward to field-testing it. What do you think? When has a text addressed you, and when have you accepted that address? Do you feel that those texts affected you religiously?