Give me that old-time religion. Give me that old-time religion.

Come on, you know that classic, Gospel tune, right?

Give me that old-time religion. It’s good enough for me.

You’re singing along in your head by now, I’m sure.

Let us pray with Aphrodite. Let us pray with Aphrodite. She wears that see-through nightie. And it’s good enough for me.

We’ll skip to everyone’s favorite refrain!

We will pray with those old druids. They drink fermented fluids. Waltzing naked through the woo-ids. And it’s good enough for me.

Okay, I’ll stop there before this gets old and blithering. This isn’t exactly the nineteenth-century hymnal from the American south, and Arlo Guthrie and Pete Seeger are clearly familiar with the term “parody.” But ironic jabs at the tune don’t exactly start with them either. They’re riffing on some collected verses of “That Real Old Time Religion,” credited to sci-fi writer Gordon R. Dickson.

The critical point here, however, is that there are some taken-for-granted assumptions about what “religion” is, or what should be understood as authentically “religious,” that could do with a little problematizing and rethinking. In other words, there’s a lot older “old-time religion” than what that song implies. And just like that simple tune, those old-time religions have been regularly remixed and mashed up since their formation.

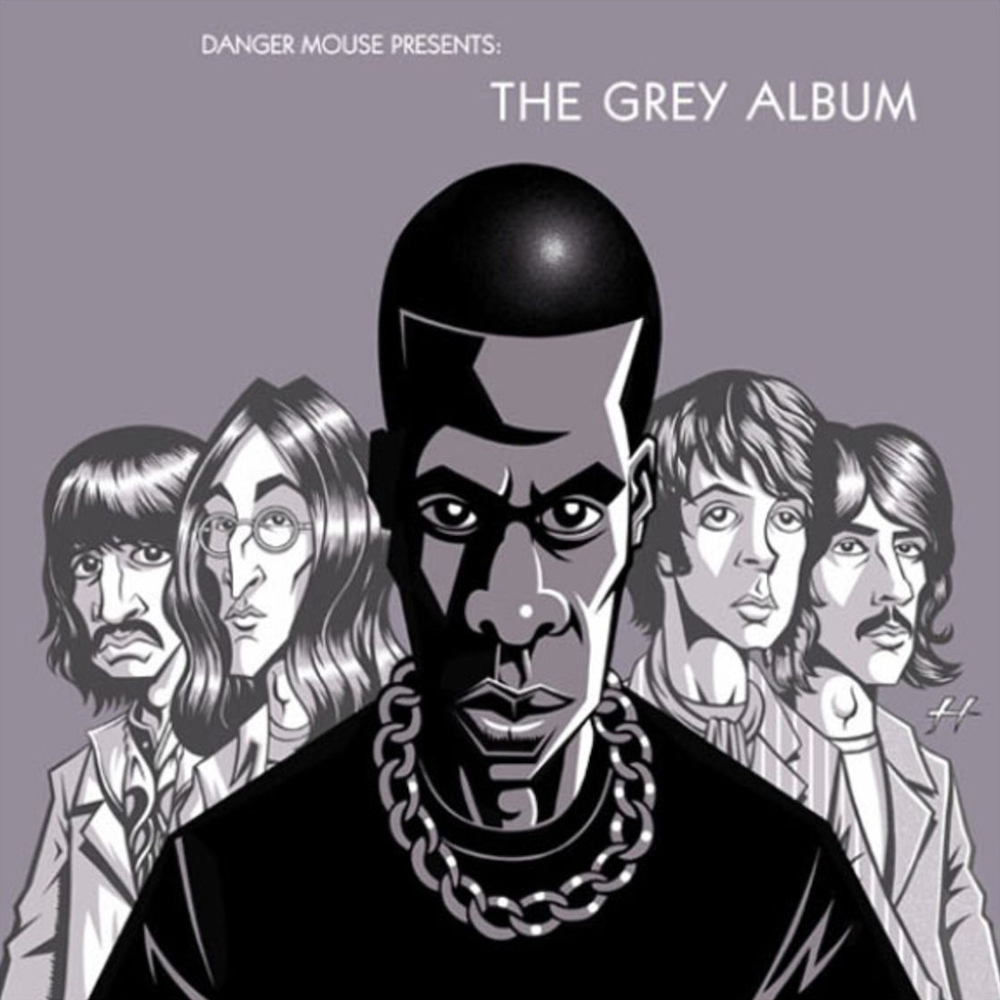

Thinking about songs like that in terms of “remix” (the use of preexisting material in the creation of something new) and “mashup” (the combination of at least two different things) probably feels more familiar and fitting than thinking about cultural traditions, practices, worldviews, or ideologies with those same terms. I’m not saying my mind still doesn’t run towards the genius of Gregg Gillis (better known as Girl Talk) or DJ Danger Mouse’s The Grey Album (2004) when I hear or read the word “mashup” today.

Promotional Artwork for The Grey Album by Justin Hampton

The latter remains one of the most classic modern examples of an A-B mashup (Jay-Z’s a cappella from The Black Album on top of The Beatles’ instrumentals from the so-called White Album), and the former is the dance-floor equivalent to a rockin’ album like Umphrey’s McGee’s Zonkey (2016). Visual artists have been doing similar things since a dyed hand touched a blank stone canvas, too. But this is the twenty-first century, folks, and historic legacies of splicing tape or rearranging visual media are reminders that audio-visual practices and products casually referred to as “remix” aren’t exactly digital age-specific – nor are they the only types of practices and productions that might be recognized as such.

The modern world is living through an age of digital media and culture – one that is shifting the content of what new media theorist Lev Manovich has referred to as the “reservoirs” of our cultural metaphors. As the pen gave way to the pixel, so too has the pixel spun on its tiny heel to start influencing the way the non-digital world might now be critically perceived and understood.

This makes up a large part of the focus in remix studies too – a growing subfield in new media that, alongside music and video applications, also considers the metaphorical extension of the concept outside of those familiar settings into culture at large. In other words, remix theory also calls for the examination of broader cultural practices and productions as “remixes,” and pushes for the consideration of how that might change the way those things are viewed and understood differently under new terminology and conceptual framing.

Curiously, religious studies hasn’t really been one of those target areas.

In part, this column is addressing that missing application, and what a critical examination in light of it might help those studying religion better understand and discern. It’s also both in dialogue with, and serving as a companion to, my current doctoral work, which deals with this application in more theoretical depth. In other words, this column is part of a larger conversation – one in which I hope you’ll join me.

And that’s what the example above is meant to enter: if you start to think about traditions as having always built upon what preceded them – remixing source material into something new or unique – then it gets a little tricky when questions are raised about this or that old-time – and implicitly, original – religion, doesn’t it?

I’ve already briefly touched on this in Nomos Journal in terms of Buddhist thought and traditions: can an original Buddhism be located if all of the later theological baggage that centuries and varying cultures attached to Siddhartha Gautama’s original teachings is shed? What, exactly, was the Buddha’s Buddhism? The allure of Stephen Batchelor’s work on Secular Buddhism aside, this isn’t as simple as the romantic line of questioning makes it sound when you start to conceive of the Buddha as a remix artist par excellence, responding to the ideas, perspectives, and practices already in existence before he placed his hand on the shady ground underneath the Bodhi’s canopy.

But that’s big picture type of stuff. How about a more tangible example before wrapping things up?

What about Thomas Jefferson?

You know, the drafter of the Declaration of Independence, the third President of the United States, the face of the highly-sought-after and convenient-to-use two-dollar bill, and the biblical cut-and-paste artist who helped Jesus shed all of that supernatural hocus pocus and get back his groove?

It’s not something typically taught in humanities or world religions courses, but when you come across The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth (or simply, The Jefferson Bible), it’s hard to not be impressed (especially if you get the chance to snag a peek of it on display at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History!).

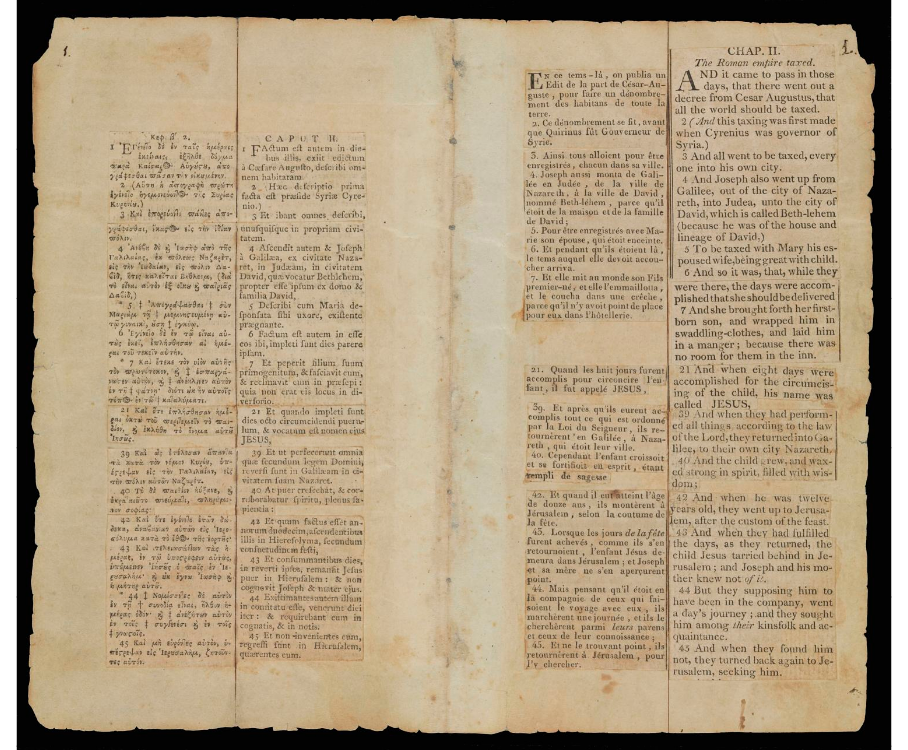

At the turn of the nineteenth century, in a move prefiguring the cut-up techniques of writers and artists like William S. Burroughs and David Bowie, Jefferson literally took a razor, glue, and his own deist and Enlightenment-influenced ambitions to multiple versions and languages of biblical text (specifically, the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John) and reworked them into a narrative of teachings devoid of miracle-working and other supernatural activity associated with Jesus, in order to simply frame him as the moral teacher Jefferson accepted him as.

Page One of The Jefferson Bible

And what of it?

Sacrilege! Blasphemy! Adulteration of a cohesive, singular narrative!

Easy battle cries among the conservative, indeed – even as some critics point to Jesus’ own propensity to spin a groovy mix. But what happens when one dives into the general composition of the books in the varying biblical canons (yes, there are several), the politics and bureaucracy that shaped them, and the agendas that determined their selective inclusion – much less the translative-interpretive processes that have further molded them? It all starts to seem very…cut and paste, doesn’t it?

But the point here isn’t to subvert theological assumptions or claims – not necessarily, at least. The point is to problematize how those assumptions and claims are devised and sustained, along with their associated practices and perspectives. This is simply how cultural creation inherently works – how various things are formed, how they develop and evolve, how they build upon what came before – and those shifting reservoirs of cultural metaphors can aid in a better understanding of those processes and the dialogic nature of cultural interaction and production.

Including religion.

And Jefferson has been far from the only person to play around with narratives and rework religious texts; Osamu Tezuka’s manga retelling of the life and times of Siddhartha Gautama, Neil Gaiman’s recent rendering of Norse mythology, and the Brick Testament all come to mind as more obvious popular cultural examples, among so many others.

Recognizing the processes underlying cultural creation can result in a more robust understanding of things like authority, authenticity, and originality, and how they might be challenged – especially in the more blatant instances like those noted above, which can encourage the consideration of even the less-than-obvious patterns shaping the ways religiosity has continued to develop.

With that, I invite you to join me in a critical application of remix theory to the study of religion as I test out developing ideas and concepts I’m working through in the larger project, highlight topics or examples that might not be making their way into it, and address current cultural trends and happenings that are particularly timely and worth noting sooner rather than later.

And I hope it will be as good enough for you as it is for me.