The recent conclusion of the new HBO series Westworld saw high volumes of praise. It has been included in some of the best of 2016 television lists and was the most popular premiere season for HBO since True Detective. The $100 million budgeted season brought Michael Crichton’s 1973 Westworld universe to life in an updated television reboot spearheaded by Lisa Joy and Rob Nolan, along with sci-fi veteran J.J. Abrams.

If you haven’t seen all of the series and intend to, be warned: spoiler alert! Westworld presents the fictional “amusement park” populated by lifelike androids (named “hosts”) playing out interactive storylines for guests’ entertainment. For a fee, guests can spend the day roaming the park, indulging in their most lurid fantasies – most popularly involving sex and death – with no consequences, as the hosts aren’t human. This raises questions around morality, which are complicated by the sympathetic presentation of the android hosts.

The Westworld park is run by Dr. Robert Ford (played by Anthony Hopkins) – the man who created the technology to build the hosts and introduced the first storylines of the park. Despite those on the mysterious administrative board who openly disagree with his methods and storylines, Ford maintains control of the park due to some rather underhand tactics. We see him using hosts as staff members (with one of the senior colleagues, Bernard, being modeled after his original partner in creating Westworld, Arnold), killing off opposing colleagues through the use of hosts, and spying on those who seek to plot against him through recording devices in the hosts. All of these actions use the hosts as pawns in his game. This presents an omniscient front to Ford, and he is at times seemingly infallible, coming off as a god-like figure. The technology of Westworld enables Ford to “play God” – to create and direct a lifelike scenario with ultimate control. This is further enforced by the inability of the hosts to change anything. They are instead stuck in their loop, destined to repeat an appealing narrative arc ad infinitum. Ford began by creating Dolores (Evan Rachel Wood), the host that would ultimately change the parameters of the park, and even his own understanding of the hosts. She is the quintessential Eve character, including the indulgence in self-awareness that ultimately destroys the dynamic of Westworld.

Dolores becoming self-aware is the aim of the park, according to Arnold, one of the original creators. Ford initially railed against this, continually creating a distinction between the hosts and humans. He has control over the hosts and uses them to control humans through the manipulation of their desires. His belief in himself as god-like is evidenced in the show’s dialogue. During the second episode (“Chestnut”), he states, “You can’t play God without being acquainted with the devil,” excusing his more questionable actions as a necessary aspect of his control. It is the world he has created that has made him a god, despite the board’s attempt to wrest control from him. As he says in the fourth episode (“Dissonance Theory”), “In here, we were gods, and you merely our guests.” A crucial part of the series is Ford’s struggle with his waning god-like control as financial interests challenge his free reign. Westworld thus offers a microcosmic world in which our assumptions and attitudes towards creation and humanity can be challenged. But, are they?

The hosts – and, increasingly, certain ones in particular – refer to their “makers” throughout the series; there is a vague discussion of a primitive religion with people worshipping mysterious men in white suits. It is revealed that these men in white are the technicians in the park, and the “religion” is a convenient cover-up for the reality of the situation. The most explicit discussion of the Judeo-Christian form of God comes in the last episode, “The Bi-Cameral Mind,” which raises the contention between religion and science most clearly for debate.

As noted above, one of the aims of the park for Arnold was for the hosts to achieve true consciousness and thus leave Eden, as it were. This striving for a disconnection from the ultimate control of their creators was perhaps the crux of the argument between Ford and Arnold. Ford’s need to exercise god-like control over the hosts is something that he has resolved and the series details his continuation of Arnold’s quest for host consciousness. Ford and Arnold, when they began creating the hosts, were experimenting with artificial intelligence and consciousness, something scientists are actually in the process of developing now. However, whether consciousness can be embedded in code and synthetic material is something still within the realms of science fiction.

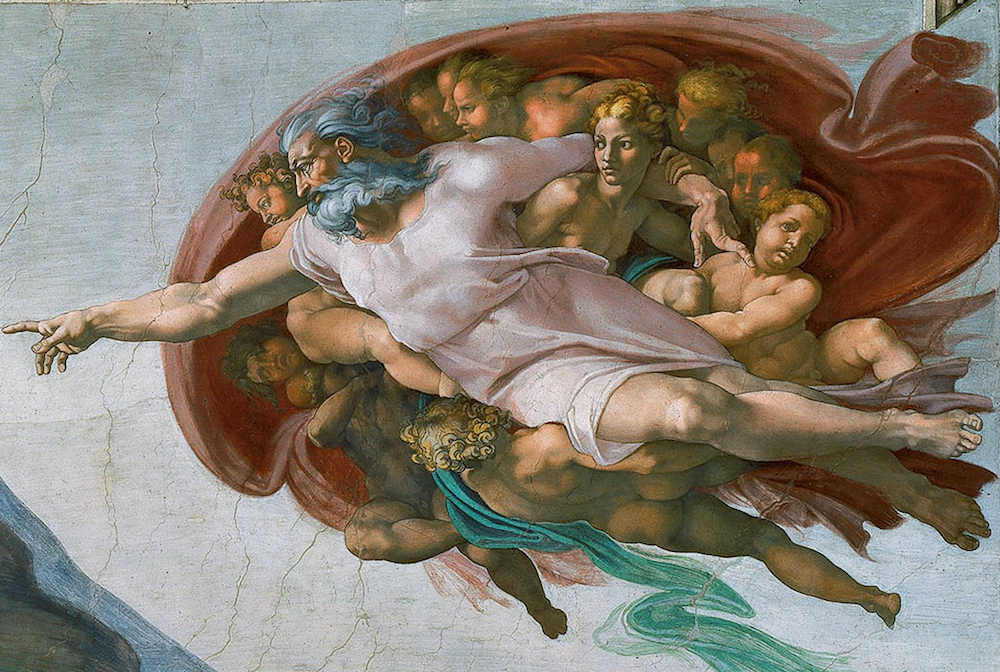

When explaining to Dolores the options she has to become “free” in the season finale, Ford shows her Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam in order to explain self-actualization, and tells her that it has been misrepresented for centuries. Few have taken heed of the shape in which God sits; Ford’s conclusion is that it is a human brain, and as he states, “The message being that the divine gift does not come from a higher power, but from our own minds.” This elicits comparisons with Shelley’s Frankenstein, where a literal spark was used to create the monster. Frankenstein’s creation becomes self-aware after reading books (symbolic of the biblical Adam eating from the Tree of Knowledge). Again, it was not God in the novel that stirred the monster to awareness, but himself. Therefore, Ford and Frankenstein are of the same mold: a fallible self-made deity that embodies the perils of subverting the natural order. Both representations also switch between the presentation of God and the devil, particularly from the perspective of their creations.

Critics have not failed to notice the engagement with questions of creation and “playing God.” Sonia Saraiya’s Variety piece on Westworld is such an example: she notes that the series “seems to be interrogating God, or some idea of God, who would produce a flawed system and observe it from an apparent distance, as the creations struggle to reconcile with and understand themselves.” Yet, she argues that the show does not make its argument explicit. It raises questions and offers no answers. There are reviewers who argue that the show is an allegory for God versus the devil and those who look at it as showing the “god in the machine.” Regardless, the storyline and dialogue make the key debate clear: we are wrestling with questions of creation and free will, which are undeniably linked to traditional religious forms, Christianity in particular.

These are questions that will become increasingly relevant as technology continues to progress and we attempt to synthesize what makes us human. Despite the fact that literary works such as Frankenstein have explored these questions before, Westworld looks at it on a wider scale, incorporating cutting-edge technology and a whole world created by men. Yet, the sympathy for the hosts doesn’t reach that elicited for Frankenstein’s monster in the novel. Perhaps this is due to the “uncanny valley” effect – as an android or robot gets closer to resembling being human, it elicits a feeling of fear or dread in humans encountering them. These creations are uncomfortably close to being human and perhaps present a threat to humanity. Westworld may present another updated version of the battle between science and religion, but the issues themselves have not changed. There will continue to be tension between the two as long as people are “playing God” and continuing to worship.